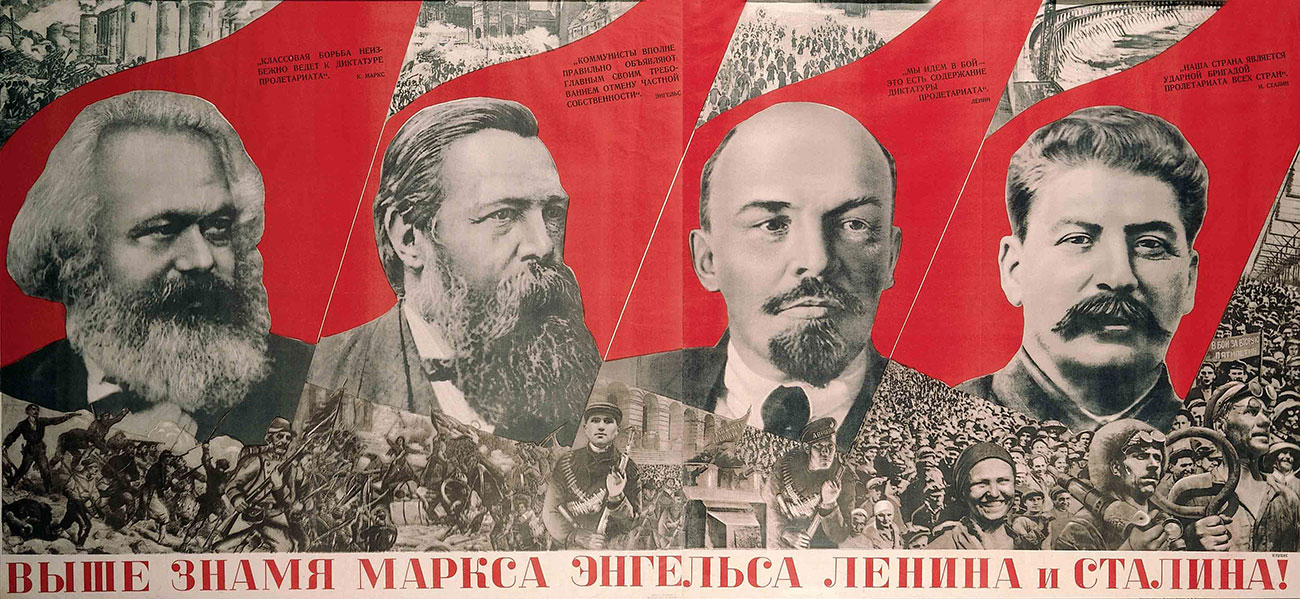

‘Few apocalyptic millenarians live to see the promised apocalypse, let alone the millennium,” writes Yuri Slezkine in “The House of Government” (Princeton, 1,104 pages, $39.95), a brilliant retelling of, mainly, the first two decades of the Soviet era in a sprawling saga centered around a famous and infamous Moscow apartment building created for the new elite. The Bolsheviks were a millenarian sect if ever there was one, as Mr. Slezkine, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, demonstrates. And, even if the millennium proved elusive, they were able to set off an apocalypse in Petrograd, then Russia’s capital, almost exactly a century ago.

That old-time millenarian ardor smolders away in “October” (Verso, 369 pages, $26.95), China Miéville’s history of what he calls the “ultimately inspiring” Russian Revolution: “This was Russia’s revolution,” he writes, “but it belonged and belongs to others, too. It could be ours. If its sentences are still unfinished, it is up to us to finish them.” It is? After the hecatombs created in communism’s name, such a call to arms is evidence of a faith untroubled when prophecy fails again and again.

Mr. Miéville is a respected Britain-based writer of science fiction but also a man of the far left, and “October” is deftly written but so skewed that the book risks tipping over into alternative history. “I am partisan,” writes Mr. Miéville, a confession that comes as no surprise; but “I have striven to be fair,” which does. Mr. Miéville’s narrative is at times—how to put this—selective. On occasion, he’s careless with facts, not least when it concerns the Bolsheviks’ January 1918 suppression of the Constituent Assembly (Russia’s last democratically elected “parliament” until the Yeltsin years): It is misleading to maintain that its membership was “chosen” before the Bolshevik coup.

That “October” is written from a sympathetic perspective is an unsettling reminder of the persistence of ideas—with roots long predating Marx—which can never safely be consigned (to appropriate Trotsky’s words) to the dustbin of history. Nevertheless this book is worth reading for its emphasis on the bitter debates within Russia’s revolutionary left over how to take advantage of the opportunity it had been given by the fall of the czar—and by the fragility of the regime that replaced him in early 1917.

When the year began, Nicholas II was clinging to his throne, Lenin was an exile in Zurich and the Bolsheviks were just one faction in a fissiparous revolutionary underground. Less than 12 months later, they were running the country—or enough of it to count. The czar was overthrown in a revolution in February (dates given are according to the Julian calendar then used in Russia). Food shortages, wider economic difficulties and general war weariness (World War I had entered its fourth year) had all reinforced the feeling shared by many Russians—even some among the ruling elite—that Romanov absolutism had had its day.

There was a wide agreement that the monarchy should go, but no consensus about what should come next. The new liberal “provisional government” had emerged out of a Duma committee during the crisis. Lacking much democratic legitimacy, it was well-intentioned, weak and well-named. A caretaker more naive than negligent, it threw open the door, but (to borrow a phrase from Engels), the hangman stood waiting outside. Dark forces poured through, including Lenin, who returned from Zurich in April, with assistance from Germany.

Russians, Lenin conceded, now enjoyed “a maximum of legally recognized rights,” but he claimed this was a capitalist con. Bolshevism was required, whether the masses realized it or not. That, eventually, was what the second, October, revolution gave them.

The excellent “Russia in Flames: War, Revolution, Civil War 1914- 1921” (Oxford, 823 pages, $39.95), by Yale’s Laura Engelstein, is a considerably more objective account than Mr. Miéville’s. It covers not just the two revolutions and their prelude, but also the civil war that ensued—a civil war that the Bolsheviks, Ms. Englestein argues, did what they could to foment. Lenin calculated that a great sorting, a “process of clarification,” as she terms it, would leave the Bolsheviks alone on top. The war turned out to be more terrible than even Lenin envisaged, but he was proved right in the end.

Lenin often was, but one interesting aspect of Ms. Engelstein’s discussion of 1917 itself is the degree to which she depicts the Bolsheviks as storm-chasers, struggling to keep pace with events they could not yet control. The successive iterations of the provisional government, the best known of which was led by the charismatic if not particularly effective Alexander Kerensky, were actually caught up in the storm.

They failed to feed the cities. They could not satisfy the demand by workers and peasants (and the soldiers recruited from those classes) for a system—collectivist and profoundly antihierarchical—very different from the liberal order they had in mind. They could—and should—have ended Russia’s unpopular, perilous participation in World War I, but didn’t. Meanwhile, democratic principles and a justified fear of both ends of the political spectrum kept Kerensky from gambling on a more authoritarian turn until it was too late.

It was a while before the Bolsheviks could take the helm. April, June and July all saw eruptions of popular discontent, which Ms. Engelstein maintains were beyond “the capacity of any political leadership to contain or direct.” The philosopher Fedor Stepun observed that Lenin’s post-exile speeches were merely “sails to catch the crazed winds of the revolution.” The Bolsheviks, writes Ms. Engelstein, were “on the margins of political life [but] . . . the margins were a good place to be.” Amid mounting disorder, “those at the center of authority, tenuous as it was, were in the process of exhausting their political credit.”

According to the Menshevik Nikolai Sukhanov (the somewhat more moderate Mensheviks and Lenin’s Bolsheviks had split in 1903), “Lenin’s group was not directly aiming at the seizure of power [in June 1917] but . . . was ready to seize it in favorable circumstances, which it was taking steps to create.” Ms. Engelstein explains how the Bolsheviks built their base, patiently gathering support among the military and in factories. They then mobilized this “relatively disciplined mass” in a manner designed to increase disorder and topple the flailing provisional government while acting as a “force for order” poised to step in when the moment came. In October, it did.

Contrary to those who assert that the workers and peasants lacked an agenda of their own, Ms. Engelstein believes they genuinely wanted social revolution—though not a Bolshevik dictatorship. But only the Bolsheviks were able “to create the architecture needed to run the successor to the autocratic state and transform the excitement of liberty into a new kind of discipline and power.” The result was totalitarian rule, in which the only “excitement” was the manipulated fervor of a cult on the march.

“Crime and Punishment in the Russian Revolution: Mob Justice and Police in Petrograd” (Harvard, 351 pages, $29.95) is an innovative study that’s about more than its title would suggest. Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, formerly a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, shows how the social breakdown that followed the February Revolution triggered a surge in crime that the provisional government could not reverse. It may be too much to argue, as Mr. Hasegawa does, that “the Bolsheviks rode a crime wave to power,” but the chaos did make it easier for them to exploit the growing vacuum in authority. The provisional government faded from shadow to ghost, essentially finished off in late October by the capture of a few buildings, a coup at first barely noticed by many in an exhausted Petrograd. Russia’s new Bolshevik rulers initially did not bother too much about crime, until devastating alcohol-fueled mayhem forced their hand, “inadvertently provoking,” claims Mr. Hasegawa, “the establishment of a new kind of police state”—one, I suspect, that was already on the way.

Helen Rappaport’s “Caught in the Revolution” (St. Martin’s, 430 pages, $27.99) is an account of 1917 as witnessed by Petrograd’s expatriate community, which was itself threatened by the lawlessness Mr. Hasegawa chronicles. A lively if sporadically florid book (“Petrograd was a brooding, beleaguered city that last desperate winter before the revolution broke”), Ms. Rappaport’s account works well as an introduction to a complicated year, but is most valuable for its record of the impressions of those who lived through it. Many of these were relatively privileged (“the servants are beginning to get stuck up with this new-born freedom”), but their observations (“I see Russia going to hell, as a country never went before”) have aged rather better than those of the enthusiasts who welcomed October’s false dawn. Rhapsodizing over workers rallying at the Bolshevik headquarters, American journalist and fellow traveler Albert Rhys Williams wrote that they were “dynamos of energy; sleepless, tireless, nerveless miracles of men.” Visiting the same place a few weeks later, a less easily impressed Frenchwoman saw “dead, doctrinaire eyes.”

Despite its title, the worthwhile “Revolution! Writings From Russia, 1917” (Pegasus, 364 pages, $27.95) features surprisingly little from the revolutionary year itself—editor Pete Ayrton includes nothing, say, from Nikolai Sukhanov or from the diaries of the novelist Ivan Bunin, a harsh critic of Bolshevism. This is only partly compensated for by Leon Trotsky’s vivid report of October 24, the “deciding night” of the Bolshevik coup—complete with the complaint, as revealing as it was dishonest, that “the Revolution is still too trusting, too generous, optimistic and light-hearted.” The next morning Lenin announced that the provisional government was no more.

The inevitable extract from John Reed’s “Ten Days That Shook the World” is a gung-ho depiction of the taking of the Winter Palace on the evening of the 25th. Somerset Maugham makes a rather less-expected appearance with a short story from “Ashenden,” a volume of tales based on his experiences as a British spy. It’s good enough, if not up to the standard set by three sentences from the book’s preface: “In 1917 I went to Russia. I was sent to prevent the Bolshevik Revolution and to keep Russia in the war. The reader will know that my efforts did not meet with success.”

Finally, “1917: Stories and Poems From the Russian Revolution” (Pushkin Press, 236 pages, $14.95) is an anthology of literary responses to Bunin’s “damn year.” Neatly chosen by Boris Dralyuk, with room for the familiar (such as Boris Pasternak) and those known less well (the sardonic Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya, who wrote as Teffi), the volume is reasonably well balanced between the October revolution’s supporters and those appalled by it. Vladimir Mayakovsky catches the millenarian mood (“We’ll cleanse all the cities . . . with a flood even greater than Noah’s”) while in “The Twelve” Alexander Blok opts for a warmer purge: “We’ll . . . set the world on fire . . . give us Your blessing, Lord!”

History made fools of the cheerleaders of revolution, but the words of those who opposed it still haunt. Anna Akhmatova resolves to stay with her “nation, suicidal” and does so, her great chronicling of Stalinist terror still to come. Marina Tsvetaeva writes of the wine flowing down “every gutter” and a “Tsar’s statue—razed, black night in its place.” Zinaida Gippius mourns the death of long longed-for liberty: “The Bride appeared. And then the soldiers / drove bayonets through both her eyes . . . The royal axe and noose were cleaner / than these apes’ bloodied hands . . . Can’t live like this! Can’t live like this!” Both Gippius and Tsvetaeva went into exile. Tsvetaeva later returned to her homeland. She hanged herself in 1941.