Latest Articles

We should not, or so we are told, judge a book by its cover, but when that book is an “Atlas of Finance”—and one of the two people featured on its cover, a clever tribute to banknotes, is Karl Marx (the other, reassuringly, is Adam Smith)—it’s reasonable to think that the image hints at what may be lurking inside….

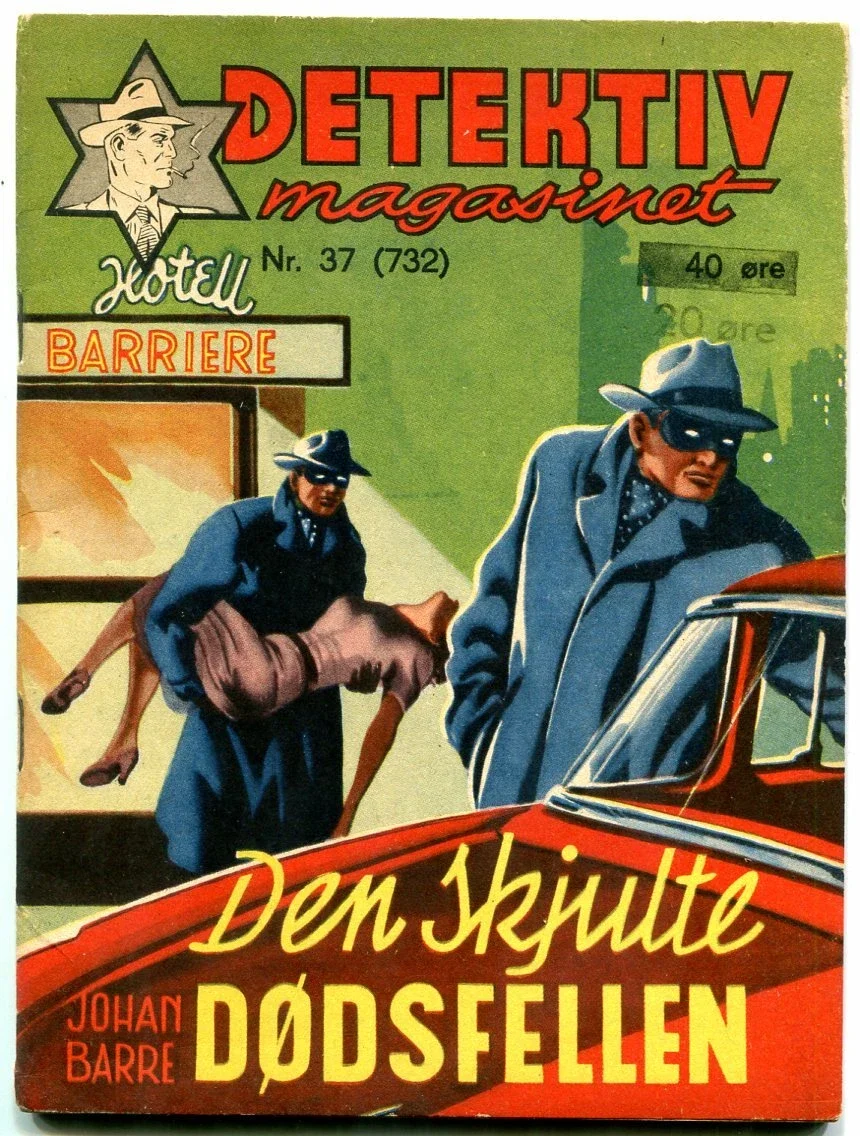

Until gang warfare and the bombings that went with it broke Sweden’s calm (the consequences of recent mass immigration have proved rougher-edged than many Swedes chose to expect), the Nordic region had for a long time been renowned for its tranquility, making it somewhat surprising that it gave birth to Nordic noir, a genre of thriller often as chilly as the realm from which it emerged. Each Nordic country has its leaders in this field, and in Norway the top dog is Jo Nesbø, hip, stylish, something of a polymath (soccer player, stockbroker, musician), and the best-selling Norwegian author of all time, renowned above all for a series of often brutal stories (recommended) featuring Harry Hole, a brilliant, awkward Oslo detective with a fondness for the bottle…

Sooner or later there comes a moment when central planners’ spreadsheets and targets run into reality. And it is rarely a happy moment. Some years ago, officials in the EU, UK, California, and other dim-bulb jurisdictions came up with the idea of imposing a quota system on automakers…

By giving online intermediaries a sizeable degree of immunity from liability for user content, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 combined a characteristically American defense of free expression with a determination to ensure that this promising new sector was not stifled by another American tradition, predatory litigation. The outcome, through blogs, social media, and countless other outlets, has been to open the public square to voices that once would never have been heard.

Re-examining the Third Reich remains, even now, essential. Its lessons are too important to be deemed safely settled. But when Richard Evans argues that the task has “gained new urgency and importance” due to the emergence of “strongmen and would-be dictators” within the world’s democracies “since shortly after the beginning of the twenty-first century,” he risks trivializing past horrors by wielding them as a weapon in the current debate over populism. That’s unless he has Vladimir Putin in mind, which would make for a very different discussion…

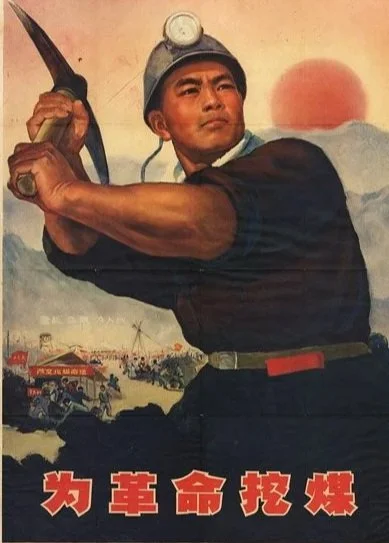

Wicked, grubby old King Coal, they said, was on his last legs.

Weeks before the signing of the Paris Climate Accord at the end of 2015, Carbon Tracker (“aligning capital market actions with climate reality”) estimated that if the world was to meet the climate target set out in the agreement, then, according to the International Energy Agency’s “450” scenario, “the production from … existing coal mines is sufficient to meet the volume of coal required … It is the end of the road for expansion of the coal sector.”

I was in a large, packed room in the Hilton. A conference held in June by the Cato Institute and an Argentine free-market think tank, Libertad y Progreso, had entered its final hours. Elon Musk had just spoken — remotely. Now self-styled anarcho-capitalist Javier Milei, Argentina’s president since December, had turned up, clad in a suit, not his trademark leather jacket, and, considerably calmer than his reputation, was giving a speech…

In Rupert Brooke’s best-known poem, a soldier says that if he dies, there will be "some corner of a foreign field/That is for ever England." As I discovered nearly 30 years ago, such corners, dating from 1918 and 1919, can be found in a cemetery in Archangel (Archangelsk) in Russia’s far north. In her latest book, British journalist and historian Anna Reid explains how they came to be there.

Writing in a recent Capital Letter about degrowth — an ideology revolving around the reorientation of the global (particularly in richer parts of the world) economy away from the pursuit of growth — I wanted to stress that this is not an outlier viewpoint shared only by the straitjacketed, which could be safely ignored.

And so I modestly repeated a point I had made in an earlier article on degrowth:

[D]egrowth has made inroads into the thinking of a significant cohort of scientists, economists, NGOs, activists, and writers. Signs of interest in it, if only at the periphery, can be detected in both bureaucratic and political circles, including the European Union and the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change…[F]ormer Obama energy secretary (and Nobel laureate) Steven Chu…has argued for “an economy based on no growth or even shrinking growth.”

On July 2, the Guardian published an article by Olivier De Schutter. He is a Belgian academic, the UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights. He wants us to “shift our focus from growth to humanity.”

Early-stage electric vehicle (EV) manufacturer Fisker, Inc. has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Of itself, that’s no scandal. Early-stage companies fail all the time. But the rise and fall of Fisker (and that of its predecessor) is a story of our times, and worth a closer look. Fisker’s predecessor, Fisker Automotive,was founded in 2007 by, to quote his X header, a “risk taker, innovation loving, protocol challenging designer and entrepreneur who turns dreams to reality & never gives up.” This modest fellow is a Danish designer well-known for his work with Aston-Martin and BMW. His name — guess — is Fisker, Henrik Fisker.