Area 51 Revisited

National Review Online, May 23, 2003

The famous "black mailbox" is, these days, white. It is battered, chipped, and covered with graffiti, but white, definitely white, not black at all — a suitable symbol for Area 51, a place where legend and reality never quite seem to match. To find it, drive north from Las Vegas into the Nevada desert, bleak and broiling at the time of my visit, blistering in the late August sun, an empty, strangely lovely place of dust devils, triple-digit temperatures, and massively overheated imaginations. Highway 93 will take you most of the way. Just past the supermarket at Ash Springs, turn left at the intersection onto that stretch of Highway 375 now officially (thank you, Governor Miller!) known as the Extraterrestrial Highway. No little green men, but a large green sign — decorated, naturally, with a couple of flying saucers — tells the visitor that this is no ordinary scenic route. This is a drive where it is wise to watch the skies as well as the road.

The mailbox itself is another 20 miles farther along. It stands, a solitary sentinel in the desert, just to the left of the highway. A dirt track heads southwest, to the mountains in the distance and, much nearer, to a far more formidable obstacle, the boundary of a vast forbidden zone: Area 51, the secret installation that some call Dreamland.

Area 51! The name follows the numbering pattern established for mapping the old nuclear-testing site that it, alarmingly, adjoins. The notoriety dates from that moment, sometime in the early 1990s, when America's interest in UFOs, never a field reserved solely for the sane, tipped over into outright mania — a mania exploited by the entertainment industry to create a series of movies and TV shows that simultaneously fed off, and fed, the narratives and obsessions of those who believed E.T. had come for real. The result was to create an echo chamber of the ludicrous, where fiction, fantasy, and (very rarely) fact bounced off one another to create ever-amplifying myth, paranoia, and pre-millennial speculation. For some, the story centered on the sweaty, delusional sexual psychodrama of all those probing, prying, prurient abductions; for others it was a blend of gearhead fantasy and conspiracy theory centered on a mysterious, lonely base baking in the Nevada sun.

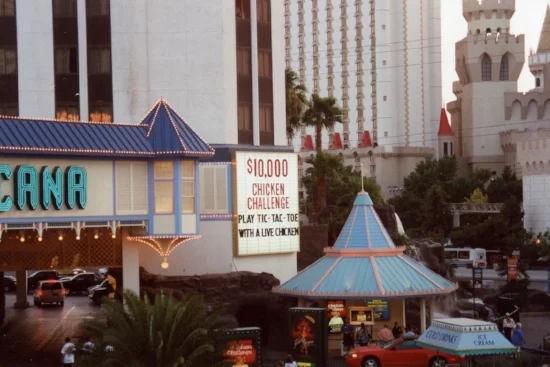

Area 51! It was a video game, a book (many, many books, actually, including Area 51, Area 51: The Reply, Area 51: The Truth, Area 51: Excalibur, Area 51: The Mission, Area 51: The Sphinx, and Area 51: The Grail), and a rap CD by the Body Snatchaz. It was the subject of sci-fi drama, numerous documentaries, frequent articles, and wild, wild rumors, all fed by tall tales and repeated sightings of lights in the sky — enigmatic, hovering, darting, pulsating, unexplained, all colors, all shapes, and, for the credulous, all meanings. It was, inevitably, a place where Mulder and Scully came calling and it was, only slightly less predictably, the base from which Will Smith and Jeff Goldblum saved the world in Independence Day.

Area 51! Depending on who you chose to believe, it was a top-secret testing ground for the U.S. Air Force, a treasure house of extraterrestrial technology, a morgue for little green (well, gray actually) corpses, or, more cheerfully, a facility (ever since a treaty signed with Eisenhower in 1954) for aliens who were still alive. More lurid still, there was talk of genetic experimentation, of ghastly unnatural cocktails of human and alien DNA, and of subterranean vats filled with body parts and other unknown horrors.

Subterranean vats filled with body parts? If that's not enough to put off uninvited visitors to Area 51, a locally produced pamphlet warns what the U.S. government will do to those who stray too close:

When you approach the boundary… there are signs on both sides of the road — Do Not Pass The Signs or you will be arrested on a charge of trespassing on the Nellis Bombing and Gunnery Range. The fine for a first offense is $600… You will see two tripod mounted surveillance cameras. You may also see guards in white jeep Cherokees or champagne colored Ford pick-ups watching you from nearby locations. As long as you do not violate the boundary, they have no authority to interfere with your activities. If you hike near the border — do not pass any of the orange posts that mark the boundary!

Well, that sounded like way too much trouble, the sort of challenge more suited to a fearless investigative reporter than to me. Craven and cautious, I rejoined Highway 375 and headed further west, to Rachel, Nev., home of the Little A'Le'Inn.

Rachel is a slight, scrappy settlement with a population of under 100 — an encampment more than a town, little more than a few trailers and a Baptist church dumped in the middle of the high desert plain. Except for the alien invasion just across the horizon, not a lot is going on in this burg. For entertainment, there's checking the readings on the radiation-monitoring station (a reminder of all those nuclear tests), hanging out at the Quik Pik convenience store, and, of course, the Little'A'Le'Inn (formerly the Oasis, Club 111, the Stage Stop, the Watering Hole, and the Rachel Bar and Grill), the Silver State's best-known intergalactic diner/motel, home of the "World Famous Alien Burger" ("served with lettuce, tomato, pickle, onion, and our Special Secret Alien Sauce") and notorious epicenter of Area 51 intrigue.

The diner ("earthlings," a sign says, are "welcome" — phew!) itself is impossible to miss. Alien figures peep out through its windows, and a tow truck is parked outside — a small flying saucer hanging forlornly from its hoist. To enter, go through the door invitingly marked "Notice — Cancer & Leukemia cases… Possible Compensation Available!" (another souvenir of those pesky nuclear tests) and you will find yourself in a large, low-ceilinged dining room with a pool table, a bar, and the biggest collection of alien ephemera outside the flea markets on Jupiter.

There are rubber aliens, plastic aliens, glow-in-the-dark aliens, inflatable aliens, gray, green, purple, and orange aliens, aliens in T-shirts, an alien in a dress, and mom, pop, and junior alien all sharing a comfortable chair. The walls are lined with more — alien yo-yos, alien cigarette lighters, alien ashtrays, alien sippy cups, alien guitar frets, alien playing cards, alien beer coolers, alien beer mugs, alien sunglasses, alien jewelry, alien key rings, alien refrigerator magnets, alien postcards, alien Christmas decorations, alien baseball caps — and the T-shirts, as countless, it seems, as the stars in the sky: "Area 51 — it doesn't exist and I wasn't there."

For more dedicated enthusiasts, there are books, magazines, pamphlets, videos (yes, that old autopsy film — again), and, lining the walls, those inevitable blurred, ambiguous pictures of lights in the sky that are always a feature of places such as these. And then there are the bumper stickers praising Newt Gingrich and attacking that hopeless man from Hope.

Gingrich? Clinton? There is a sense that this is a place that time may be passing by, that the Little A'Le'Inn may be becoming the Little A'Le'Out. Back in the 1990s, Rachel was a hotbed of alien activity (or, at least, the search for alien activity), complete with a research center/trailer (close to the Quik Pik) run by one Glenn Campbell (not to be confused with Glen Campbell — one "n," Rhinestone Cowboy). The town played host to UFO seminars, UFO Friendship Campouts, UFO technicians (supposed ex-Area 51 employee Bob Lazar — worked on alien technology, saw mysterious alien writing), Ufologists, UFO tourists, and, of course, Larry King. Yes, Larry King — UFO Cover-Up? Live From Area 51. You missed it?

But that was then. The saucers will return, doubtless, to soar again over our popular culture, but UFOs, for now, appear to be going the way of the hula hoop, and it's going to take more than Spielberg's revealingly lackluster Taken (complete with Area 51 references) to bring them back. That's not to say that Rachel's visitors have been reduced solely to the ranks of the extraterrestrial. Some humans — true believers or just the curious — are still coming to scrutinize the skies, to peer at the base, and to dodge the fearsome "cammo dudes" who guard its perimeter. Others show up just to giggle, cheerfully buying the tchotchkes that celebrate a phenomenon in which they do not really believe.

The small group of diners at the Inn was mainly European, strangers in a stranger land, laughing as they chowed down on alien burgers and surveyed the alien kitsch. They had found their alien Graceland, a desert theme park of the absurd, another piece of exuberant Americana to treasure and to mock, a spectacle impossible to imagine in their own constrained, more sober continent. Gamely, a member of the Inn's staff told her story. She had, naturally, seen those "lights in the sky." That's not so peculiar in the vicinity of an air base where new planes and other hardware are tested, but no one seemed to mind.

It's telling that Glenn Campbell has moved on. They remember him with a smile at the Quik Pik, but the self-dubbed "Psychospy" has abandoned Rachel for cyberspace. According to his website, Area 51 is now a "has-been." The Research Center "has moved on to broader issues." And so has the U.S. The saucer frenzy of the 1990s was self-indulgence for safer times, play-acted paranoia suitable for an era when the country believed it had no real enemies. Now the adversary is visible, his strength, ironically, the product not of some highly advanced technological civilization, but of something almost more alien — a primitive, theocratic fanaticism that should have been buried centuries ago. Under these circumstances, talk of an extraterrestrial menace seems embarrassingly frivolous. Besides, nowadays most people rather like the idea of secret bases.

So long as they are on our side.