Tsar Power

When George W. Bush looked Vladimir Putin in the eye, he was, the president famously said, able to get “a sense of his soul.” The president was neither the first nor the last to see what he wanted in this enigmatic, laconic man.

Read MoreWhen George W. Bush looked Vladimir Putin in the eye, he was, the president famously said, able to get “a sense of his soul.” The president was neither the first nor the last to see what he wanted in this enigmatic, laconic man.

Read MoreCaravan! Van der Graaf Generator! Yes! Genesis! To Englishmen of a certain age, just reading some of these old names will take them back to an era when progressive rock haunted the turntable, songs stretched out endlessly (three minutes would barely be enough for a proper guitar solo), and lyrics—well, they took themselves more seriously than

About halfway through Britain’s long Blair nightmare, I went to two dinners where Boris Johnson was billed as the guest speaker. Each time he was eagerly awaited: a man on the rise, a gifted journalist, an engaging and eccentric television personality, a Tory MP. Each time he was late. When he eventually turned up — all scarecrow hair and unconvincing excuses — he explained that he’d left his notes behind. He pressed on regardless in that blend of Drones Club and High Table that he has made his own. Both speeches were funny, sharp — and more or less identical. Johnson knows, as Winston Churchill knew, that a spontaneous speech takes plenty of preparation. A book by Boris on Winston — first-name politicians both — ought to make sense. Like Churchill, Johnson is phenomenally ambitious, unusually resilient, and remarkably skilled at using showmanship, élan, and his pen to build, refine, and reshape his image.

It’s a shame, then, that The Churchill Factor is not very good. The grand old stories roll on grandly by, but there’s little that’s new for those who know their Churchill, and not enough depth for those who don’t. But if you’re interested in Johnson, this book is well worth a look. If Boris was someone to watch back when I listened to him make one speech two times, he is much more so today. He has since twice won election as mayor of London — no small feat for a Conservative — and is poised to reenter Parliament in the 2015 general election. From there he will be well placed to run for the Tory leadership in the likely event that David Cameron has just led his party off a cliff.

Johnson’s success owes a great deal to the manner in which he has defused his potentially toxic poshness. Like the hapless Cameron, Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson went to the wrong school (Eton) and the wrong university (Oxford), and then capped the whole disgraceful gilding by joining the Bullingdon Club, an Oxford gang of the rich and sporadically destructive brought to politically tricky national attention some years ago when an ill-wisher leaked the club’s 1987 photo — a snapshot of archaic finery, Flashman attitude, and Sloane Ranger hair, a photo in which both Cameron and Johnson appeared.

Cameron has tried to deal with this embarrassment of privilege by recasting his public persona (very) gently downscale. The more charismatic Johnson, gambling that Brits take more pleasure in eccentricity than in reverse snobbery, has moved in the opposite direction, putting on a display of wild toff rococo — a bit of Wooster, a spot of Biggles, a touch of Raffles — that has left class warriors too amused to be chippy.

It’s a performance that rests heavily on Johnson’s way with words. His speeches are punctuated by slang, dated terminology, and madcap verbal construction. An accusation of infidelity was famously, if inaccurately, dismissed as an “inverted pyramid of piffle.” But what works in a sound bite palls over the course of a book. Tootling, monstering, wonky, squiffily, tosser, prang, perv, titfer, snortingly, bonkers, bunging — crikey, Boris, hold the shtick already. Unnecessary adjectives and superfluous adverbs run wild. Metaphors meander. A promising description of Churchill’s house — crammed with researchers, writers, and secretaries — as “one of the world’s first word processors . . . a gigantic engine for the generation of text” dragged on so long that all I wanted was the delete button. To be sure, there are splendid moments (“the French were possessed of an origami army: they just kept folding”), but they are swamped by verbosity.

So it’s ironic that the best section of the book is Johnson’s superb analysis of how Churchill’s oratory was put together, what it was meant to convey, and why it worked as well as it did. Sadly, Johnson himself ignores two key Churchillian tricks — short words over long, “Anglo-Saxon pith” over intruders with Latin and Greek origins — burdening the readers of this book with such treats as chiasmus, philoprogenitive, and eirenic, words that probably played little part in the small talk of Alfred the Great.

But these ten-guinea words are sly demonstrations of erudition, deployed for political, not literary, effect. Boris may play Wooster to beguile the plebs, but he wants them to understand that he is no upper-class twit. At the same time, he needs his audiences to feel that he is an inclusive sort of fellow, with them if not necessarily of them. So he brings his readers alongside him on trips to the sacred sites — to Chartwell, to the House of Commons, to kind Nurse Everest’s grave — while throwing in glimpses of a life that he invites them to share, if only by proxy: lunch at the Savoy, a birthday bash for a hedge-fund “king” at Blenheim Palace. Condescending, yes, but cleverly disguised. Only rarely does the mask slip, and the text sprouts tics more typical of history books written for the late-Victorian nursery: “Those were the days, you see, when there was no moral pressure on MPs to have a ‘home’ in the constituency.”

“You see”? Well, I suppose I do. Thank you, sir.

Notionally, Johnson has written this book to revive ebbing memories of Churchill and to remind his readers that, whatever some cruder Marxists might have to say about history’s being driven by “vast and impersonal economic forces,” one man can make a difference. Based primarily on a fine retelling of the events of 1940, Johnson makes a strong, if unsurprising, case that Churchill was such a man.

But Boris’s real objective in writing about Churchill is to promote Boris. Wisely, he doesn’t try to push Churchill comparisons — hosting the London Olympics doesn’t quite rank with seeing off Hitler — but there’s enough there for a satisfactory subliminal message. So Johnson tells the story of a man comfortable in his unorthodoxies, a statesman who was larger than life, and, like a certain twice-elected mayor of London that I could mention, larger than party.

In recent years, Johnson has positioned himself as offering a more robust, less politically correct version of David Cameron’s “modernized” conservatism, more libertarian, not so committed to environmentalist piety, pro-immigration (for its purported qualities as an agent of economic growth), and a booster of London’s cosmopolitanism, too, but not so respectful of multiculturalist orthodoxy. Johnson portrays Churchill, not unreasonably, as an early-20th-century Whig, an optimist, a Progressive of sorts.

But the old imperialist is not safely pigeonholed. Johnson defends his hero against the accusation that he was a warmonger and — as he should — places some of Churchill’s rougher views within the context of his times. Occasionally (not as uncharacteristically as fans of the allegedly plain-speaking Johnson like to believe), Boris simply dodges the issue: There is nothing on Churchill’s response to the Bengal famine of 1943, startlingly callous then and now.

Johnson — clearly conscious that times have moved on for the island race — takes care to signal that, despite his obvious admiration for Churchill, he himself is no reactionary. He distances himself from some instances of the more “unpasteurized” Churchill, but not too far. The last lion is still idolized by many of those who will be picking the next Conservative leader, an election evidently on Johnson’s mind. Why else tread quite so carefully on the question of Churchill’s complicated views on a united Europe, that most treacherous of Tory topics?

But tread carefully Johnson does. He has his eyes on the prize. Churchill would have understood.

I first visited Estonia—or more specifically, its capital, Tallinn—in August 1993, two years after the small Baltic state regained its independence after nearly half-a-century of Soviet occupation. Tallinn was in the process of uneasy, edgy transformation. The Soviet past was not yet cleanly past. It was still lurking in the dwindling Russian military bases. It was still visible in the general shabbiness, in the rhythms of everyday life, and, above all, in the presence of the large Russian settler population, a minority that Vladimir Putin now eyes hopefully, if not necessarily realistically, for its troublemaking potential.

Totalitarian colonial rule had been replaced by a national democracy, the ruble had been succeeded by the kroon, and free-market reformers were at the helm; but the new government was operating in the rubble of the command economy. There was no spare cash to smooth the transition to capitalism. Inflation had exceeded 1,000 percent during the course of the previous year, savings had been wiped out, the old Soviet enterprises were dying, and the welfare net was fraying.

Yet in Tallinn there was a discernible sense of purpose, buttressed by memories of the prosperous nation prewar Estonia had been. What people wanted, I was told, was a “normal life.” That was a phrase that could be heard all over the former Eastern Bloc in those days, a phrase that damned the Soviet experience as an unwanted, unnatural interruption and resonated with dreams of that elusive Western future. Life was tough in Tallinn, but there were hints of better times to come. If the country was to be rebuilt, this was where the turnaround was taking shape.

But Sigrid Rausing went somewhere else in 1993, to a place far from the hub of national reconstruction, a place where the inhabitants had little idea of what could or should come next, a bleak place—poor, even by the demanding standards of post-Soviet Estonia—where nationhood was misty and visions of the future were still obscured by the wreckage of an alien utopia. Rausing, a scion of one of Sweden’s richest families, was a doctoral student in social anthropology. To gather material for her thesis, she spent a year on the former V. I. Lenin collective farm on Noarootsi, a remote peninsula on the western Estonian coast.

Noarootsi had once been inhabited by members of the country’s tiny Swedish minority, most of whom had been evacuated to the safety of their ancestral homeland by Estonia’s German occupiers shortly before the Red Army returned in 1944. The final minutes before their departure were caught on film: the exiles-to-be assembled on a beach, Red Cross representatives mingling with smiling SS officers. Baltic history is rarely straightforward.

Rausing’s thesis formed the basis of her History, Memory, and Identity in Post-Soviet Estonia: The End of a Collective Farm, an academic work published by Oxford University Press 10 years ago. This was never a book destined to top the bestseller lists, but for anyone able to weather the clouds of jargon that drift by—“the effect was to emphasize the experience of oppositions in the form of a homology”—it offers a sharp, intriguing, and unexpectedly wry portrait of what Rausing refers to as the “particular post-Soviet culture of 1993-94, the culture of transition and reconstruction,” a culture that no longer exists.

Rausing has now reworked the topic of her time in Noarootsi into Everything Is Wonderful, a personal, intimate account of that year in which she largely dispenses with academic analysis—indeed, there are moments when she pokes gentle fun at its absurdities—and gives her considerable lyrical gifts free rein. Graduate-school prose now finds itself transformed into passages of austere beauty. They describe a landscape that reminds her of Sweden, only “deeper, vaster, and sadder”; more than that, they portray a people adrift. There is something of dreaming in her writing, images that haunt. Spring returns, and

the children were outside again, playing and shouting in the long twilight, until there was an almost deafening din echoing between the blocks of flats. One day someone burnt the old brown grass strewn with rubbish between the blocks, and the children kept up their own private fires deep into the night.

There is a subplot too, tense and awkward, sometimes expressed in not much more than a hint, that surrounds the position of Rausing herself, an attractive thirty-something Swedish heiress inserted into this exhausted husk of a community and, for a while, lodging with the heavy-drinking, possibly/probably lecherous Toivo and his long-suffering wife, Inna. Ingmar Bergman, your agent is on the line.

That’s not to say that Rausing neglects the broad themes of her academic research. As she notes, the two books “overlap to some degree,” and they have to. Without repeating some of the background covered in the first volume, isolated, depopulated Noarootsi—with its Soviet dereliction, abandoned watch-towers (the peninsula had been in a restricted border zone), emptied homesteads, and taciturn, enigmatic inhabitants scarred by alcoholism and worse and speaking a language of a complexity Rausing struggled to grasp—would have seemed like nothing so much as the setting for a piece of post-apocalyptic gothic. So Rausing provides a brief, neatly crafted, and necessary guide to Estonia’s difficult and troubled history, neglecting neither the obvious horrors nor the subtler atrocities, such as the attempted cultural annihilation represented by the wholesale destruction of Estonian literature. Tallinn Central Library lost its entire collection of books—some 150,000 of them—between 1946 and 1950.

Sometimes, traces of that history—forbidden for so long—come crashing through the silence. Ruth, 76, a Seventh-Day Adventist, tipped by tyranny into something more unhinged than eccentricity, hands Rausing a handwritten retelling of her life: “Devilish age, sad age. Schoolchildren also spies . . . life as leprosy.” But Everything Is Wonderful is a book in which the story lies mainly beneath the surface. Old ways linger on amid new realities. There is a new cooperative store, but the old Soviet shop hangs on, “selling household stuff as well as some food, pots and pans, exercise books, shoes if they got a consignment, and ancient Russian jars of jams and pickles with rusty lids and falling-off labels.”

Throughout the brutal winter, heating is intermittent. Heating bills are no longer subsidized, but the majority of villagers “patiently” pay them nonetheless. New habits creep in. Empty Western bottles and other packaging are displayed in apartments, demonstrations of “a connection with the West, a way of expressing the new normal”—that word again, that “normal” in which most had yet to find their feet. Meanwhile, Swedes bring hand-me-down help and the suspicion that they might be looking to reclaim a long-lost family home.

Rausing is a participant in this drama. We learn of her fears, her loneliness, of her wondering what she is doing in this distant Baltic corner, and of her small pleasures, too (“the tipsy sweet happiness of strawberry liqueur”). But she is a spectator as well, and a perceptive one, not least when it comes to the profoundly uncomfortable relationship between Estonians and the Russian minority. The latter are resented as colonists, yet caricatured in terms that remind Rausing of the “natives” of the “colonial imagination: happy-go-lucky, hospitable people lacking industry, application, and predictability.” She dines in a restaurant in a nearby town, where “the atmosphere was a little strained between a Russian group of guests and the few Estonians in the room.” Later, Rausing learns that the “only” Russians living in the “comfortable Estonian part of town” are deaf and dumb; they are “outside language,” as she puts it, and thus able (she theorizes) to “assimilate . . . through muteness.”

That sounds extreme, but the scars of the past were still very raw back then. Sometime in the mid-1990s, I watched a senior member of the Estonian government bluntly explain the facts of Estonia’s (to borrow a Canadian phrase) twin solitudes to a delegation of Swedish investors. There was, he said, little overt trouble between ethnic Estonians and the country’s Russians, but there was little contact either: “We don’t get on.”

Rausing’s tone is quiet, often wistful, marred only by interludes of limousine liberalism—apparently there was something “liberating” in the way the locals didn’t care too much about their possessions, which is easy enough, I imagine, when those possessions were, for the most part, Soviet junk—including an element of disdain for the market reforms that were to work so well for Estonia. The prim pieties of Western feminism also make an unwelcome appearance. Watching a pole dancer in a rundown resort town summons up concerns over “objectification,” but Rausing’s response to reports of a topless car wash in Tallinn is endearingly puzzled and—so Swedish—practical: “Really strange, particularly given the Estonian climate.”

But this should not detract from Rausing’s wider achievement. Her book is the last harvest yielded up by that old collective farm, and the finest.

Richard Ropner (Harrow), Royal Machine Gun Corps

On August 3, 1914, twenty-two of England’s best public school cricketers gathered for the annual schools’ representative match. The game ended the following evening. Britain’s ultimatum to Germany expired a few hours later. Seven of those twenty-two would be dead before the war was over. Anthony Seldon and David Walsh’s fine new history of the public schools and the First World War bears the subtitle “The Generation Lost” for good reason.

Britain neither wanted nor was prepared for a continental war. Its armed forces were mainly naval or colonial. The regular army that underwrote that ultimatum was, in the words of Niall Ferguson, “a dwarf force” with “just seven divisions (including one of cavalry), compared with Germany’s ninety-eight and a half.”

Britain’s more liberal political traditions, so distinct then—and now—from those of its European neighbors, had rendered peacetime conscription out of the question, but manpower shortages during the Boer War and growing anxiety over the vulnerability of the mother country itself led to a series of military reforms designed to toughen up domestic defenses. These included the consolidation of ancient yeomanry and militias into a Territorial Force and Special Reserve. The old public-school “rifle corps,” meanwhile, were absorbed into an Officers’ Training Corps and put under direct War Office control.

Most public schools signed up for this, and by 1914 most had made “the corps” compulsory. Some took it seriously. Quite a few did not. Stuart Mais, the author of A Public School in Wartime (1916), wrote that Sherborne’s prewar OTC was seen as “a piffling waste of time . . . playing at soldiers” that got in the way of cricket. Two decades later, Adolf Hitler cited the OTC to a surprised Anthony Eden (then Britain’s foreign secretary) as evidence of the militarization of Britain’s youth. It “hardly deserved such renown,” drily recalled Eden (in his unexpectedly evocative Another World 1897–1917), “even though the light grey uniforms with their pale blue facings did give our school contingent a superficially Germanic look.”

And yet this not-very-military nation saw an astonishing response to the call for volunteers to join the fight. By the end of September 1914 over 750,000 men had enlisted. But where were the officers to come from? A number of retired officers returned to the colors, and the Territorials boasted some men with useful experience, but these were not going to be close to sufficient numbers. The army turned to public-school alumni to fill the gap. In theory, this was because these men had enjoyed the benefit of some degree of military training, however inadequate, with the OTC, but in truth it was based on the belief of those in charge, themselves almost always former public schoolboys, that these chaps would know what to do. Looked at one way, this was nothing more than crude class prejudice; looked at another, it made a great deal of sense. In the later years of the war, many officers (“temporary gentlemen” in the condescending expression of the day) of humbler origins rose through the ranks, but in its earlier stages the conflict was too young to have taught the army how best to judge who would lead well. In the meantime, Old Harrovians, Old Etonians, and all those other Olds would have to do.

To agree that this was not unreasonable implies a level of acceptance of the public school system at its zenith utterly at odds with some of the deepest prejudices festering in Britain today. British politics remain obsessed with class in a manner that owes more to ancient resentments than any contemporary reality. A recent incident, in which a columnist for the far left Socialist Worker made fun of the fatal mauling of an Eton schoolboy by a polar bear (“another reason to save the polar bears”), is an outlier in its cruelty, but it’s a rare week that goes by in which a public school education is not used to whip a Tory cur, as David Cameron (Eton) knows only too well.

Under the circumstances it takes courage to combine, as Seldon and Walsh do, a not-unfriendly portrait of the early twentieth-century public schools (it should be noted that both men are, or have been, public schoolmasters) with a broader analysis that implies little sympathy for the sentimental clichés that dominate current British feeling—and it is felt, deeply so—about the Great War: Wilfred Owen and all that. It is not necessary to be an admirer of the decision to enter the war or indeed of how it was fought (I am neither) to regret how Britain’s understanding of those four terrible years has been so severely distorted over the past decades. Brilliantly deceptive leftist agitprop intended to influence modern political debate has come to be confused with history.

Oh! What a Lovely War smeared the British establishment of the 1960s with the filth of Passchendaele and the Somme. Similarly, the caricature of the war contained in television productions such as Blackadder Goes Forth (1989) and The Monocled Mutineer (1986) can at least partly be read as an angry response to Mrs. Thatcher’s long ascendancy. Coincidentally or not, the late 1980s also saw the appearance of The Old Lie: The Great War and the Public-School Ethos by Peter Parker. For a caustic, literary, and intriguing—if slanted—dissection of these schools’ darker sides, Parker’s book is the place to go.

Seldon and Walsh offer a more detailed and distinctly more nuanced description of how these schools operated, handily knocking down a few clichés on the way: There were flannelled fools aplenty, but there was also the badly wounded Harold Macmillan (Eton), “intermittently” reading Aeschylus (in Greek) as he lay for days awaiting rescue in a shell hole. Aeschylus was not for all, but a glance at the letters officers wrote from the front is usually enough to shatter the myth of the ubiquitous philistine oaf. There was much more to the public schools than, to quote Harrow’s most famous song, “the tramp of the twenty-two men.”

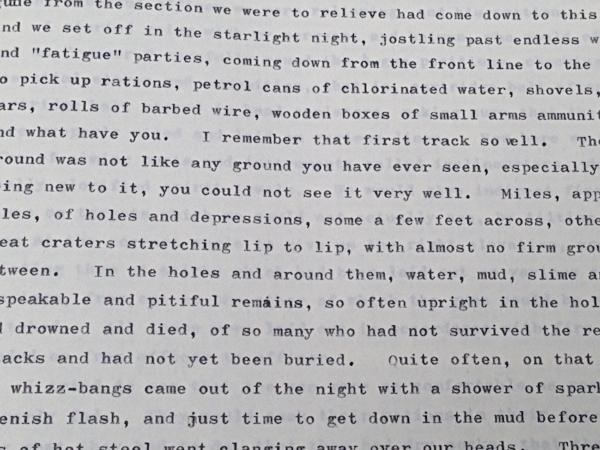

But however harsh a critic he may be (“that men died for an ethos does not mean that the ethos was worth dying for”), Parker is too honest a writer not to acknowledge the good, sometimes heroic, qualities of these hopelessly ill-trained young officers and the bond they regularly forged across an often immense class divide with the troops that they led. “I got to know the men,” wrote my maternal grandfather Richard Ropner (Harrow, Machine Gun Corps) in an unpublished memoir half a century later, “I hope they got to know me.” In many such cases they did. It is tempting to speculate that such bonds (easier to claim, perhaps, de haut than en bas) may have been more real in the eyes of the commanders than of the commanded, but there is strong evidence to suggest that there was nothing imaginary about them. Men died for their officers. Officers died for their men.

My grandfather owned a set of memorial volumes published by Harrow in 1919. Each of the school’s war dead is commemorated with a photograph and an obituary. It is striking to see how frequently the affection with which these officers—and they almost all were officers—were held by their men is cited. Writing about Lieutenant Robert Boyd (killed at the Somme, July 14, 1916, aged twenty-three), his company commander wrote that Boyd’s “men both loved him and knew he was a good officer—two entirely different things.” This subtle point reflects the way that the public school ethos both fitted in with and smoothed the tough paternalism of the regular army into something more suited to a citizen army that now included recruits socially, temperamentally, and intellectually very different from that rough caste apart, Kipling’s “single men in barricks.”

The public schools relied heavily on older boys to maintain a regime that had come a long way from Tom Brown’s bleak start. This taught them both command and, in theory (Flashman had his successors), the obligations that came with it. That officers were expected both to lead and care for their men was a role for which they had thus already been prepared by an education designed, however haphazardly, to mold future generations of the ruling class. Contrary to what Parker might argue, these schools had not set out to groom their pupils for war. But the qualities these institutions taught—pluck, dutifulness, patriotism, athleticism (both as a good in itself and as a shaper of character), conformism, stoicism, group loyalty, and a curious mix of self-assurance and self-effacement—were to prove invaluable in the trenches as was familiarity with a disciplined, austere, all-male lifestyle.

There was something else: The fact that many of these men had boarded away from home, often from the age of eight, and sometimes even earlier, meant that they had learned how to put on a performance for the benefit of those who watched them. A display of weakness risked transforming boarding school life into one’s own version of Lord of the Flies. That particular training stayed with them on the Western Front: “I do not hold life cheap at all,” wrote Edward Brittain (Uppingham), “and it is hard to be sufficiently brave, yet I have hardly ever felt really afraid. One has to keep up appearances at all costs even if one is.” It was all, as Macmillan put it, part of “the show.”

There are countless examples of how stiff that upper lip could be, but when Seldon and Walsh cite the example of Captain Francis Townend (Dulwich), even those accustomed to such stories have to pause to ask, who were these men?: “Both legs blown off by a shell and balancing himself on his stumps, [Townend] told his rescuer to tend to the men first and said that he would be all right, though he might have to give up rugby next year. He then died.”

Pastoral care was all very well, but the soldiers also knew that, unlike the much-resented staff officers, their officers took the same, or greater, risks that they did. This was primarily due to the army’s traditional suspicion that the lower orders—not to speak of the raw, half-trained recruits who appeared in the trenches after 1914—could not be trusted with anything resembling responsibility, but it also reflected the officers’ own view of what their job should be. And so, subalterns (a British army term for officers below the rank of captain), captains, majors, and even colonels led from the front, often fulfilling, particularly in the case of subalterns, a role that in other armies would be delegated to NCOs. The consequences were lethal. Making matters worse, the inequality between the classes was such that officers were on average five inches taller than their men, and, until the rules were changed in 1916, they always wore different uniforms too. The Germans knew who to shoot. The longer-term implications of this cull of the nation’s elite may have been exaggerated by Britons anxious to explain away their country’s subsequent decline, but the numbers have not: some 35,000 former public schoolboys died in the war, a large slice of a small stratum of society.

Roughly eleven percent of those who fought in the British army were killed, but, as Seldon and Walsh show, the death rate among former public schoolboys (most of whom were officers) ran at some eighteen percent. For those who left school in the years leading up to 1914 (and were thus the most likely to have served as junior officers) the toll was higher still. Nearly forty percent of the Harrow intake of the summer of 1910 (my grandfather arrived at the school the following year) were not to survive the war. Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War (2010) by John Lewis-Stempel is an elegiac, moving, and vivid account of what awaited them. Lewis-Stempel explains his title thus: “The average time a British Army junior officer survived during the Western Front’s bloodiest phases was six weeks.”

To Lewis-Stempel, a fierce critic of those who see the war as a pointless tragedy, the bravery and determination of these young officers made them “the single most important factor in Britain’s victory on the Western Front,” a stretch, but not an altogether unreasonable one, and he is not alone in thinking this way. The British army weathered the conflict far better—and far more cohesively—than did those of the other original combatants, and effective officering played no small part in that.

Lewis-Stempel attributes much of that achievement to the “martial and patriotic spirit” of the public schools, a view of those establishments with which Parker would, ironically, agree, but that is to muddle consequence with cause. Patriotic, yes, the schools were that, as was the nation—being top dog will have that effect. But, like the rest of the country, they were considerably less “martial” than Britain’s mastery of so much of the globe would suggest. A public school education may have provided a good preparation for the trenches, but it did not pave the way to them. That so many alumni came to the defense of their country in what was seen as its hour of need ought not to form any part of any serious indictment against the schools from which they came. That they sometimes did so with insouciance and enthusiasm that seems remarkable today was a sign not of misplaced jingoism, but of a lack of awareness that, a savage century later, it’s difficult not to envy.

And when that awareness came, they still stuck it out, determined to see the job done. Seldon and Walsh write that “It was the ability . . . to endure which underpinned the former public schoolboys’ leadership of the army and the nation.” Perhaps it would have been better if they had had been less willing to endure and more willing to question, but that’s a different debate. To be sure, there was plenty of talk of the nobility of sacrifice—and of combat—but, for the most part, that was evidence not of a death wish or any sort of bloodlust, but of the all too human need to put what they were doing, and what they had lost, into finer words and grander context.

And that they clung so closely to memories of the old school—to an extent that seems extraordinary today—should come as no surprise. These were often very young men, often barely out of their teens. School, especially for those who had boarded, had been a major part of their lives, psychologically as well as chronologically. “School,” wrote Robert Graves (Charterhouse), “became the reality, and home life the illusion.” And now its memory became something to cherish amid the mad landscape of war.

They wrote to their schoolmasters and their schoolmasters wrote to them. They returned to school on leave and they devoured their school magazines. They fought alongside those who had been to the same schools and they gave their billets familiar school names. They met up for sometimes astoundingly lavish old boys’ dinners behind the lines, including one attended by seventy Wykehamists to discuss the proposed Winchester war memorial. The names of three of the subalterns present would, Seldon and Walsh note, eventually be recorded on it.

So far as is possible given what they are describing, these two authors tell this story dispassionately. Theirs is a calm, thoroughly researched work, lacking the emotional excesses that are such a recurring feature of the continuing British argument over the Great War. That said, this book’s largely uninterrupted sequence of understandably admiring tales could have done with just a bit more counterbalance. For that try reading the recently published diaries written in a Casualty Clearing Station by the Earl of Crawford (Private Lord Crawford’s Great War Diaries: From Medical Orderly to Cabinet Minister) with its grumbling about “ignorant and childish” young officers arousing “panic among the men [with] their wild and dangerous notions.”

Doubtless the decision by Captain Billy Neville (Dover College) to arrange for his platoons to go over the top on the first day of the Somme kicking soccer balls is something that Crawford would have included amongst the “puerile and fantastic nonsense” he associated with such officers. Seldon and Walsh, by contrast, see this—and plausibly so—not as an example of Henry Newbolt’s instruction to “Play up! play up! and play the game!” being followed to a lunatic degree, but rather as an astute attempt by Neville to give his soldiers some psychological support. “His aim was to make his men, who he knew would be afraid, more comfortable.” Better to think of those soccer balls than the enemy machine guns waiting just ahead. Nineteen thousand British troops were killed that day, including Neville. He was twenty-one.

Crawford was a hard-headed, acerbic, and clever Conservative, but occasionally his inner curmudgeon overwhelmed subtler understanding, as, maybe, did his location behind the lines, fifteen miles from where these officers shone. Nevertheless, one running theme of his diaries, the luxuries that some of them allowed themselves (“yesterday a smart young officer in a lofty dogcart drove a spanking pair of polo ponies tandem past our gate”) touches on a broader topic—the stark difference in the ways that officers and men were treated—that deserves more attention than it gets in Public Schools and the Great War. Even the most junior officers were allocated a “batman” (a servant). They were given more leave, were paid a great deal more generously, and, when possible, were fed far better and housed much more comfortably than their men. Even in a more deferential age, this must have rankled. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Parker dwells on this issue in more detail than Seldon and Walsh, but, fair-minded again, agrees that what truly counted with the troops was the fact that “when it came to battle [the young officers’] circumstances were very much the same as their own.”

They died together. And they are buried together, too, not far from where they fell. As the founder of the Imperial War Graves Commission explained, “in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, the officers will tell you that, if they are killed, they would wish to be among their men.”

A century later, that’s where they still are.

Richard Ropner - Random Recollections (unpublished - 1965)

In the months leading up to the Bolshevik Revolution, Joseph Stalin was, recalled one fellow revolutionary, no more than a “gray blur.” The quiet inscrutability of this controlled, taciturn figure eventually helped ease his path to some murky place in the West’s understanding of the past, a place where memory of the horror he unleashed was quick to fade. Pete Seeger sang for Stalin? Was that so bad?

This bothers Paul Johnson, the British writer, historian and journalist. Hitler, he notes with dry understatement, is “frequently in the mass media.” Mao’s memory “is kept alive by the continuing rise . . . of the communist state he created.” But “Stalin has receded into the shadows.” Mr. Johnson worries that “among the young [Stalin] is insufficiently known”; he might have added that a good number of the middle-aged and even the old don’t have much of a clue of who, and what, Stalin was either.

Mr. Johnson’s “Stalin: The Kremlin Mountaineer” is intended to put that right. In this short book he neatly sets out the arc of a career that took Soso Dzhugashvili from poverty in the Caucasus to mastery of an empire. We see the young Stalin as an emerging revolutionary, appreciated by Lenin for his smarts, organizational skills and willingness to resort to violence. Stalin, gushed Lenin, was a “man of action” rather than a “tea-drinker.” Hard-working and effective, he was made party general secretary a few years after the revolution, a job that contained within it (as Mr. Johnson points out) the path to a personal dictatorship. After Lenin’s 1924 death, Stalin maneuvered his way over the careers and corpses of rivals to a dominance that he was never to lose, buttressed by a cult of personality detached from anything approaching reason.

Mr. Johnson does not stint on the personal details, Stalin’s charm (when he wanted), for example, and dark humor, but the usual historical episodes make their appearance: collectivization, famine, Gulag, purges, the Great Terror, the pact with Hitler, war with Hitler, the enslavement of Eastern Europe, Cold War, the paranoid twilight planning of fresh nightmares and a death toll that “cannot be less than twenty million.” That estimate may, appallingly, be on the conservative side.

Amid this hideous chronicle are unexpected insights. Lenin’s late breach with Stalin, Mr. Johnson observes, was as much over manners as anything else: “a rebuke from a member of the gentry to a proletarian lout.” And sometimes there is the extra piece of information that throws light into the terrible darkness. Recounting the 1940 massacre of Polish officers at Katyn, Mr. Johnson names the man responsible for organizing the shootings—V.M. Blokhin. He probably committed “more individual killings than any other man in history,” reckons Mr. Johnson. Ask yourself if you have even heard his name before.

To be sure, Mr. Johnson’s “Stalin” will not add much new to anyone already familiar with its subject’s grim record. It is a very slender volume—a monograph really. Inevitably in a book this small on a subject this large, the author paints with broad strokes, sweeping aside some accuracy along the way. Despite that, this book makes a fine “Stalin for Beginners.”

As Mr. Johnson’s vivid prose rolls on, the gray blur is replaced by a hard-edged reality. Stalin’s published writings were turgid, and he was no orator, but there was nothing dull about his intellect or cold, meticulous determination. As for his own creed, Mr. Johnson regards him as “a man born to believe,” one of the Marxist faithful, and maybe Stalin, the ex-seminarian, was indeed that: Clever people can find truth in very peculiar places.

But what he was not, contrary to the ludicrous, but persistent, myth of good Bolshevik intentions gone astray, was the betrayer of Lenin’s revolution. As Mr. Johnson explains, Stalinist terror “was merely an extension of Lenin’s.” Shortly before the end of his immensely long life, Stalin’s former foreign minister (and a great deal else besides), Vyacheslav Molotov, reminisced that “compared to Lenin” his old boss “was a mere lamb.” Perhaps even more so than those of Stalin, Lenin’s atrocities remain too little known.

Over to you, Mr. Johnson.

He ate poisoned cakes and he drank poisoned wine, and he was shot and bludgeoned just to make sure, but still Rasputin lived on. And that gives me just enough of an excuse to use the mad, almost indestructible monk to begin an article about a mad, possibly indestructible currency. The euro has crushed economies, wrecked lives, toppled governments, broken its own rule book, made a mockery of democracy, defied market economics, and yet it endures, kept alive by the political will of the EU’s elite, fear of the alternative, and the magic of a few words from Mario Draghi, the president of the European Central Bank (ECB) back in July 2012.

Speaking to an investment conference, Draghi said that, “within our mandate” (a salute to watchful Germans), the ECB was “ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro.” “Believe me,” he added, “it will be enough.” Those few words, and their implication of dramatic market intervention, did the trick. Financial markets calmed down, and there are now even faint hints of economic recovery in the worst corners of the euro zone’s ER. And all this has happened without the ECB’s actually doing anything. Simply sending a signal sufficed.

The crisis has been declared over by the same Brussels clown posse that always declares the crisis over. They may be right, they may be wrong, but a calm of sorts has descended on the euro zone — not peace exactly, but quiet, punctuated occasionally by tremors that may be aftershocks, but could be omens of fresh chaos ahead.

That makes this a good time to take a look at The Fall of the Euro, a guide to the EU’s vampire currency by Jens Nordvig, global head of currency strategy for the Japanese investment bank Nomura Securities. If you are looking for a quick, clear, accessible account, free from financial mumbo-jumbo, that explains how the euro came to be, why trouble was always headed its way, what was done when the storm broke, and what might happen next, this book (which was published last autumn) is an excellent place to start.

It is written from the point of view of a market practitioner. Nordvig is not too fussed about the deeper European debate. He mainly wants to know what works. Here and there he will nod politely to democratic niceties, but this is a book where worries over lost sovereignty are dismissed as “sentimental.” Overall, Nordvig is a supporter of closer European integration (“a noble ideal,” he maintains — it isn’t, but that’s another story), but one with considerably less time for illusions than most in his camp.

And the euro, he argues, was built — and run — on illusions, the illusion that Germany was Italy, Italy was Portugal, and Portugal was Finland, the illusion that one size would fit all. Its creation was a “reckless gamble.” Politics prevailed over economics. No one made any preparations for the rainy day that could never come. The foundations for catastrophe were laid, and then built on by regulators, policymakers, and financial-market players only too happy to believe that the impossible was possible. Imbalance was piled on imbalance, and a shared currency masked the nightmare developing underneath. Employed by Goldman Sachs at the time, Nordvig saw how markets viewed the euro zone as an indivisible whole. But Greece was still Greece. And Germany was still Germany.

“Policy makers,” writes Nordvig, “can attempt to circumvent the basic laws of economics, but over time, the core economic truths take their revenge.” Unsustainable boom was followed by what has seemed, until recently, like permanent bust.

Nordvig does a fine job of explaining how the euro zone has been kept intact since the storm first broke, but he focuses more on the how than on the implications. Thus he relates how some of what has been done appears to “circumvent” a clear legal prohibition on European Central Bank financing of public-sector deficits, but seems to see that as more of a curiosity than cause for concern. But concern is called for: The EU’s combination of lawlessness at the top (remember how the Lisbon Treaty was used to “circumvent” those French and Dutch referenda) and tight control over everyone else has been a hallmark of tyranny through the ages.

Then again, financial types generally focus, understandably enough, on the financial rather than the political. But when the two look to be at risk of colliding, market attention shifts. Nordvig suspects that the euro zone may be getting closer to one of those moments.

He sees the euro zone as having emerged from its travails into what is now a state of “vulnerable equilibrium.” But to work properly, it needs substantially deeper fiscal and budgetary integration — something resembling the set-up that underpins monetary union in the U.S. He’s right about that, and that he is goes a long way toward explaining why euroskeptics are so opposed to the single currency. A realist, Nordvig concedes that the political support for such a step is simply not there, and he’s right about that too. New Yorkers might grumble about the way that, courtesy of the federal government, they effectively send cash to Mississippi, but they accept that their two states are in the same American boat. Germans look across at the Greeks (and other mendicants) and realize that they have been conned into bailing out a bunch of foreigners. That’s why, when Germany accepted the need for some sort of fiscal union to keep the euro zone in one piece, it insisted (as Nordvig explains) on an arrangement that falls far short of how such a union is usually understood. The Fiscal Compact that ensued is intended to minimize deficit spending in euro-zone member states rather than give Brussels additional spending power, spending power that could have been used to help out the battered periphery. It is no “transfer union.”

All that is left for the euro zone’s weaker performers is yet more austerity (sensibly enough, Nordvig sees the current currency regime as akin to a gold standard, and not in a good way), adding further bite to the deflationary crunch which these countries face. And it’s a crunch made worse by the perception, both fair and unfair, that it is being imposed on them from “abroad.” Greece is not Germany. And nor is France.

With bailouts resented in the euro zone’s more prosperous north, and austerity loathed elsewhere, it’s surprising how passive voters have been. There are plenty of explanations for this, but Nordvig is right to stress fear of the turbulence that abandoning the euro might unleash (a fear reinforced by establishment propaganda and the failure of many of the euro’s critics to articulate a credible alternative). A residual attachment to that “noble idea” of closer European union has also played a part as has, Nordvig notes, the determination of the dominant parties of center right and center left to hang onto the single currency. That’s something that has left anti-euro, but otherwise mainstream, voters struggling to find an outlet for their discontent.

That said, the prolonged economic grind is increasingly forcing voters in the direction of less respectable parties (such as France’s Front National) that believe that the euro zone and EU need much more than a mild course correction (the FN would pull France out of the euro). If these parties gain significant ground in May’s elections to the EU parliament (the betting is that they will), the danger (or opportunity) is not that they will overthrow the prevailing consensus in the EU parliament (they have neither the numbers nor the cohesion to do that), but that their success will shove their mainstream opponents in a more euroskeptic direction back home. Credibly enough, Nordvig identifies the possibility of a revolt within the political center (which could take very different forms: The Finns, say, may decline to support another bailout, while the Greeks might eventually turn away from austerity) as another potential block on the road to the closer integration that the single currency needs.

Even if the euro zone’s leadership does manage to fumble its way to agreeing on how closer integration could be secured — a deal that would inevitably involve massive transfers of sovereignty to Brussels — it will not be easy to push such a package through without the approval of a referendum or two. On past form, and in the electorate’s present mood, that will not be easy.

But, warns Nordvig, “if further integration is not feasible, some form of breakup is inevitable.” Nordvig may be sympathetic to the European project, but he is too much of a realist to pay too much attention to the Brussels myth that there is no alternative to preserving the euro “as is.” Specifically, he rejects the argument that, just because a “full-blown” breakup would be cataclysmic (as Nordvig convincingly shows, it could well be), all forms of breakup must be too. That’s a claim he heretically and correctly regards as little more than “a convenient tool to bind the euro zone together” and one, moreover, that has been used to stifle any proper analysis of what the costs and benefits of, say, a particular country’s quitting the euro might be. Such a departure, he believes, could be engineered “without intolerable pain.”

In understanding what Nordvig means by this, pay attention to his observation that “the cost of exit may be more concentrated around the transition phase, while the cost of sticking with the euro accumulates gradually over time.” Jumping out of a burning building is never easy, but it often beats the alternative.

Nordvig deftly summarizes what the costs and benefits of that jump might be, concluding that quitting the euro would be very tough for Ireland, Greece, Portugal, and Spain, easier than perhaps expected for France and Italy, and easiest (although far from problem-free) for Germany (I’d agree). That’s a position that logically takes him not too far (although he doesn’t quite arrive there) from support for a division of the single currency into northern and southern euros, something that has, in my view, long been the way to go. According to Nordvig, however, the most likely quitter is a country reduced to a state of such excruciating agony (not only in that burning building, but on fire) that exiting the euro finally comes onto the agenda. That is highly unlikely to be Germany, the nation most able to cope, inside the euro and out.

So what happens next? Suitably cautious in the face of such an uncertain environment, Nordvig lays out a number of different scenarios. While accepting, as he should, that political turmoil could upend everything, Nordvig appears, on balance, to conclude that the German austerity model will prevail, that a transfer union will be avoided, and that the euro zone’s laggards will trudge their way to an excruciatingly slow recovery. My own suspicion is that this assumes too much patience on the part of the periphery. Pushed both by common sense and fear of an increasingly unruly electorate, its governments will start a slow-motion revolt against what remains of the hard-money ECB that the Germans were once promised. Still in thrall to the cult of “ever closer union,” and terrified of the alternatives, Germany’s leadership will acquiesce. In fact there are clear signs that this process may be well underway.

This will lead to another of the scenarios sketched out by Nordvig. Loose money will try to fill some of the gap left by the transfer union that never was, and will do so just well enough to enable the euro to survive, but as a currency that is more lira than deutsche mark. That will be yet another betrayal of taxpayers in Europe’s north, while leaving the continent’s south still trapped in a system that does not fit.

And for what?

For decades, the notebooks of Gareth Jones (1905-35), a brilliant young Welshman murdered in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, were stashed away in his family’s house in South Wales, only to be retrieved by his niece, Siriol Colley, in the early 1990s. By that time, Jones, once a highly promising journalist and an aide to a rather better-known Welshman, David Lloyd George, had largely vanished from history. But two books that appeared around then, Robert Conquest’s The Harvest of Sorrow (1986) and Sally J. Taylor’s Stalin’s Apologist (1990), gave a hint of what was to come.

In the first, a groundbreaking account of the manufactured famine that devastated Soviet Ukraine in 1932-33, Conquest told how Jones had gotten off a Kharkov-bound train, tramped through the broken Ukrainian countryside, and, on his return to the West, sounded the alarm about what Ukrainians now call the Holodomor (literally, to “kill by hunger”). Conquest explained how Jones’s “honorable and honest reporting” was trashed not only by Soviet officialdom, but also by Western journalists in the Soviet capital, a squalid episode discussed in more depth in Stalin’s Apologist, a biography of Walter Duranty, the New York Times’s Pulitzer Prize-winning correspondent in Moscow.

Duranty, whose relationship with the Stalin regime fueled a very well-paid career, took the lead in discrediting Jones. Claims of famine were “exaggeration” or, worse, “malignant propaganda.” Jones hit back, but to little avail. With just two years of life remaining to him, the path for his descent into historical oblivion was set. As for those three, four, five, maybe more, million deaths—well, so far as the West was concerned, nothing on that scale had happened. Sure, something bad had taken place, but to borrow Duranty’s term, there’s no omelet without breaking eggs; that’s how it goes.

It says something about the extent to which the Ukrainian genocide had been erased from Western memory that when Colley went through her uncle’s notebooks—the scribbled source material for the best English-language eyewitness reports of the famine—what caught her eye most (admittedly it had long been the source of family speculation) were later sections relating to what would ultimately be his murder in Manchuria. That was the topic that became the subject of Colley’s first book, Gareth Jones—A Manchukuo Incident (2001), a privately published volume in which only a page or two was reserved for Ukraine.

Times change. The reappearance of Gareth Jones was accelerated by the determination of many Ukrainians—free at last from imposed Soviet silence—to understand their own history. The investigation of a family tragedy broadened into an effort, helped by supportive members of the Ukrainian diaspora, to rediscover a journalist whose long-forgotten writing could be used to shape this newly independent nation’s sense of self and, more specifically, to help pull it away from Russia’s grip. It is no coincidence that Gareth Jones was posthumously awarded Ukraine’s Order of Merit at a time when Viktor Yushchenko, the most pro-Western of Ukraine’s presidents up until now, was in charge.

By then, Siriol Colley had written More Than a Grain of Truth (2005), a biography (again self-published) of her uncle, offering a fuller portrait of a man who was a blend of Zelig—on a plane with Adolf Hitler, at San Simeon with William Randolph Hearst, you name it—and Cassandra, warning of nightmares to come. Meanwhile, a website (Garethjones.org) developed by Colley’s son Nigel had evolved into an invaluable online resource for anyone wanting to know more. Interest in Jones has continued to grow. A steady flow of stories in the British press, a documentary for the BBC, an exhibition at his old Cambridge college, and much else besides, were evidence that Jones was re-entering history beyond the frontiers of Ukraine—history that (as related in the West) finally had room for the Holodomor. This shift boosted interest in Jones, but was also, in a virtuous circle, partly the product of the rediscovery of his account of that hidden genocide, an account written in accessible English rather than a Slavic tongue.

But the reemergence of Jones does not diminish the darkness that accompanied his original eclipse, a darkness that runs through Gareth Jones: Eyewitness to the Holodomor. Ray Gamache’s work does not pretend to be a comprehensive biographical study, although it features enough helpful detail to act as a reasonable introduction to Jones’s extraordinary life. And it handily knocks down a few myths along the way. To name but two, the notion of a plot by the Moscow correspondents (such as it was) should not be overstated. And Jones did not sneak onto that train to Kharkov (his journey had official approval); it was where he got off—in the middle of nowhere, into the middle of hell—that was unauthorized.

That said, this fine book’s central focus is something more specific, a perceptive, methodical, and diligently forensic examination of the articles that Gareth Jones wrote about the Soviet Union, the circumstances in which they were written, the message they were designed to deliver, and, critically, their overall reliability. The reader is left in no doubt that this courageous, intensely moral man, an exemplar of the Welsh Nonconformist conscience at its best, saw the horrors he so meticulously chronicled in his notebooks and to which he then bore witness in his journalism: “This ruin I saw in its grim reality. . . . I saw children with swollen bellies.”

This is an academic book and thus not entirely free of jargon (“journalism texts are linguistic representations of reality”) or the contemplation of topics, such as the journalistic ethics of Jones’s giving food to the starving, likely to be of scant interest off-campus. That said, Gamache’s shrewd, careful work gives an excellent sense of Jones’s powerful analytical skills and the layers of meaning contained in his plain, unvarnished prose.

Above all, this book forcefully conveys Jones’s foreboding that something wicked was headed towards the peasantry. A leftish liberal in that early-20th-century way, he had had a degree of sympathy with the professed ideals of the Bolshevik Revolution; but then, as he wrote later, “I went to Russia.” And while he found things to admire in the Soviet Union, the underlying structure of its society appalled him. He saw a ruthless Communist party astride a hierarchy of which the peasantry—relics of the past who were of use, mainly, to feed the industrial proletariat—were at the bottom. With the dislocation, the fanaticism, and the failures of the first Five Year Plan becoming increasingly obvious, Jones knew who would pay the price. References to the danger of famine begin to surface in his reporting, and by October 1932, he was writing two pieces for Cardiff’s Western Mail under the headline “Will there be soup?” In March 1933, Jones returned to the Soviet Union to find out. The rest is history.

That it took so long to be recognized as such, however, was due to more than Soviet disinformation and Walter Duranty’s lies. For as dishonest and influential as that campaign by Duranty was, some of it, even on its face, did not ring quite true—not least the tortured circumlocutions with which he buttressed his denials of famine. Writing in theNew York Times, Duranty conceded that, yes, there had been an increase in the death rate, but “not so much from actual starvation as from manifold disease due to lowered resistance.”

Phraseology like that is only sufficient to fool those who wanted to be fooled, and there were plenty in the West ready to give the Soviet Union the benefit of the doubt. Many more simply did not care. The broad outline of what was happening, if not its details, was there for anyone prepared to look. To take just a few examples, there was the reporting of Jones and a handful of others (including Malcolm Muggeridge, whose role vis-à-vis Jones was, as Gamache reminds us, a complex one); there were the stories filtering out through the diaspora; there was the relief effort being attempted by Austria’s Cardinal Innitzer. But few took much interest. After all, said Duranty later, the dead were “only Russians,” a faraway, alien people who didn’t, apparently, count for a great deal.

And there was something else. Gamache records how the Foreign Office, which had access to good information of its own about the famine, deliberately kept quiet, worried about some British engineers then being held by the Soviets—by July 1933, all had been released—and, more broadly, about damaging Britain’s relations with the USSR, a concern sharpened, Gamache suggests (perhaps too charitably), by Hitler’s arrival in power earlier that year.

Looking across the Atlantic, Gamache notes, it has been argued that plans by the Roosevelt administration to extend diplomatic recognition to the Soviet Union may well have led Washington to downplay the famine. In any event, the United States and the Soviet Union agreed to establish formal diplomatic relations in November 1933, an event fêted with a lavish dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria, where Walter Duranty was a guest of honor. In a nod to the cuisine of the Soviet homeland, borscht, a traditional Ukrainian dish as it happens, was on the menu. That evening, at least, there was soup.

If you cannot face going to Russia to see the real thing — in a dank Moscow underpass perhaps, or a broken attempt at a village — the best introduction to that nation’s drinking culture is to meet up with Venya, the narrator of Venedikt Erofeev’s Moscow to the End of the Line, a strange, bleakly comic, forbidden masterpiece of the early Brezhnev era. In the course of its first page, he drinks four vodkas, two beers, port “straight from the bottle,” and then, more vaguely, “something else.” It’s downhill from there.

In meandering, chaotic prose, Erofeev describes a drink-sodden, phantasmagoric train journey, punctuated by depictions of decay, echoes of Russia’s past, and recipes for cocktails that would make Appalachia blanch. With luck, no Russians ever drank “The Spirit of Geneva” (White Lilac, athlete’s foot remedy, Zhiguli beer, and alcohol varnish), but, as Mark Schrad, an assistant professor at Villanova University, notes in his absorbing, no less drink-sodden, not much less meandering, and even more horrifying Vodka Politics, they came close, not least during the time when Mikhail Gorbachev was cracking down on alcohol production:

“The most hard-up drinkers turned to alcohol surrogates: from mouthwash, eau de cologne, and perfume to gasoline, cockroach poison, brake fluid, medical adhesives, and even shoe polish on a slice of bread [a recipe that requires some additional preparation]. In the city of Volgodonsk, five died from drinking ethylene glycol, which is used in antifreeze. In the military, some set their thirsty sights on the Soviet MiG-25, which — due to the large quantities of alcohol in its hydraulic systems and fuel stores — was affectionately dubbed the “flying restaurant.”

It’s difficult not to smile at that, but then thoughts turn to those five dead in Volgodonsk, just a tiny fraction of a death toll from alcohol poisoning that ran into the tens of thousands, casualties of the burgeoning zapoi (a binge that lasts days or weeks) that finally lurched out of control during the economic implosion that followed the Soviet collapse. Post-Soviet Russia had little realistic alternative to the principle of shock therapy (how it was carried out is a different matter), but Schrad is right to stress the depths to which the country sank. The bottle, often filled with dubious black-market hooch, was one of the few sources of solace left. This, rather literally, added further fuel to the fire already raging through Russia’s demographics: “Average life expectancy for men — 65 at the height of [Gorbachev’s] anti-alcohol campaign in 1987 — plummeted to only 62 in 1992. Two years later, it dipped below 58.”

According to Schrad, “the best estimates are that in the 1990s, Russians quaffed some 15 to 16 liters of pure alcohol annually,” a figure that, tellingly, does not appear to be so different today, and is well above the “eight-liter maximum the World Health Organization deems safe.” These are per capita data, kindly averages that mask the extent to which it is mainly men who are drinking to excess, a fact that helps explain why Ivan can expect to live some ten years less than Natasha.

All those liters might alarm even skeptics legitimately suspicious of the WHO’s nannyish side, but the results for other nations offer context, if not reassurance. According to the WHO, Russia’s alcohol consumption in 2011 was near the top of the international range, but it was far from the only country to cross the eight-liter threshold (the U.S. clocked in at 9.44 liters, the U.K. at 13.37). Beyond obvious differences in standards of health care, Russia’s catastrophe was clearly due to something subtler than the overall volume of alcohol consumed. What may have mattered more is that so much (6.88 liters) of the Russian tally was accounted for by spirits (the U.K., no stranger to the binge, came in at 2.41). That suggests that what is drunk (and, more specifically, how it is drunk) counts. Schrad quotes another Erofeev, the contemporary writer Viktor: “The result, not the process, is what’s important. You might as well inject vodka into your bloodstream as drink it.”

A disaster of this magnitude — on some estimates as many as half a million Russians each year are dying as a consequence, directly or indirectly, of alcohol abuse — was not the product of economic implosion alone. Other hard-drinking countries in the former Soviet space went through comparable traumas in the 1990s. But none, with the possible exception of Ukraine, a land long exposed to the worst pathologies of Russian rule, tippled quite so far over the edge. There was something that singled Russia out, and it predated the collapse of Communism by a very long time. As early as 1967, the rapid growth of alcohol consumption in the post-war years — something helped along by growing prosperity and a state that had replaced the anti-alcohol militancy of the earlier Soviet period with a sharp appreciation for the revenues that vodka brought in — had taken annual per capita consumption of pure alcohol (exclusive of bootleg samogon) to 9.1 liters. Drinking was an accessible pleasure for a society that had cash, but — in a still-austere Soviet Union — not much to spend it on. There was also something else: Vodka may have been used to soothe the pain associated with the collapse of Communism, but it had also been a way of anaesthetizing people through the dreary decades that preceded that long-overdue change, decades in which aspiration was stifled, life was hard, and futility was the norm. Under the circumstances, why not drink up?

But boozing one’s way through Brezhnev was also a reversion to older patterns of behavior that the early Bolsheviks — in some respects a puritanical bunch — believed they had swept away for good. In 1913, the wicked old empire’s per capita consumption stood at just under that perilous eight liters, and that was less of a gulp than the swigging that had preceded it a few years before. Vodka was not only a familiar presence in the Russian troika, it had also become one of its drivers, a wild, erratic, and destructive driver, to be sure, but one so powerful that attempts to unseat it contributed to the fall of both Gorbachev and (Schrad makes the case well) quite possibly the last czar too.

How demon drink grabbed the reins is the question that lies at the heart of Vodka Politics, which comes with the subtitle “Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State.” That “secret” is something of an overstatement (as Schrad acknowledges, this is far from being the first work on this topic), but it is a claim not inconsistent with his occasionally excitable style (“While the cold wind howled beyond the Kremlin walls . . . ”). As told by a chatty and engaging author, this is Russia’s past seen, one might say, through the bottom of a glass, a perspective that is certainly skewed (sometimes too much so — the liberal Decembrist rebels of 1825 were rather more than an “inebriated Petersburg mob”) but is undeniably fascinating and often enlightening.

Schrad’s central thesis is simple enough: It is the tale of vodka as a “dramatic technological leap” (like a cannon, it has been said, compared with the “bows and arrows” of wine, beer, and more traditional drinks) that was adopted by Russia’s rulers (and how — if it’s epics of alcoholic excess that you are after, this is the book for you) and then ruthlessly exploited by them, a story that, with brief interruptions, has continued essentially unchanged for more than half a millennium.

Ivan III (reigned 1462–1505) was the first to establish a state monopoly on distillation, but Schrad prefers to credit his grandson, a rather more terrible Ivan, with “being perhaps the first to realize the tremendous potential of the liquor trade.” In between debauches and atrocities (if you are on the hunt for Grand Guignol, chronicled with faintly unseemly relish, this is also the book for you), he outlawed privately held taverns and replaced them with state-run kabaks. This was the next stage in, as Schrad describes it, the evolution of a system of “macabre beauty” under which the state built itself up by using mechanisms designed to increase the dependence of its subjects on a product — cheap to produce, profitable to sell, potent to consume — that gave them the illusion of release only to enslave them still further.

The catch was that the state itself became dependent on this dependency. At the height of the Russian empire, vodka funded a third of what became known as the state’s “drunken budget.” Toward the end of Soviet rule, vodka’s contribution was roughly a quarter. And vodka was a pleasure too tempting to be confined to those at the bottom of the heap. It seeped through all social classes, high and low, at immense cost to the country’s progress then and now, its spread facilitated by the unwillingness of the czarist and Soviet regimes to allow room for a civil society strong enough to push back, not to speak of their failure to nurture a nation in which the bottle would not seem like quite such an attractive escape.

So what now? With Russia’s economy in somewhat better shape and (thanks, primarily, to higher oil prices) vodka’s percentage contribution to the state’s income having shrunk to comparatively modest mid single digits, the chances — one might think — ought to be good that something serious could be done to address a public-health cataclysm that has not gone away. After all, the ostentatiously sober Vladimir Putin is at the helm. Some measures have indeed been taken, but this is still Russia, a top-down place where the people come last, where vodka profits accrue to the state and to the well-connected, a country where outside, maybe, some metropolitan centers, hope remains in short supply.

Moscow to the End of the Line draws to a close with the drunken Venya missing his stop and returning to the point at which he began.

And then things get worse.

Statue of Liberty, June 2009 © Andrew Stuttaford

There is usually a moment in the course of a typical English picnic of drizzle, hard-boiled eggs, and chill, when someone looks up at the gray, unyielding sky and brightly announces that the weather is “clearing up.” If Josef Joffe attends English picnics, he would be that someone.

In this cheery take on America’s prospects, Joffe, the editor of Die Zeit, looks around and ahead and decides that, for all its problems, the U.S. will do just fine. He reminds us that pundits and politicians have been awaiting the end of America since its beginning. In itself, of course, this proves nothing: Time passes, facts change; what once was set in stone ends up slithering on sand. Joffe takes care to say that the failure to come true of previous prophecies of America’s decline “does not mean that [one] never will,” but, given the broader themes of this book, those words — and a handful of others like them — are the equivalent of the quick-fire muttering that accompanies some car commercials, caveats that no one is meant to notice.

Joffe, a shrewd and subtle analyst, is on firmer ground when he turns his attention to the nature, origins, and history of “declinism.” Predictions of an American tumble, he argues, frequently owe more to the dreams, fears, or ambitions of those who made them than to any reasonable calculation of what the future might hold. There have always been those, abroad, who have taken comfort in the thought that this over-mighty giant — and dangerous inspiration — might be faltering. Here at home, however, prophecies of doom are often intended to be self-defeating, designed to change behavior — enough already with the twerking, enough already with the neglect of missile defense — that would otherwise lead to catastrophe.

And declinism is a powerful political tool (fear sells) that has long been used and abused. Joffe relates how insurgent presidential candidates have a habit of basing their campaigns on existential threats that have a way of disappearing by the time, four years later, that the insurgent-turned-incumbent, “first Jeremiah, now redeemer,” is seeking reelection by a country where it is, again, morning. This record of apocalyptic bunkum does not mean that every politician’s prediction of approaching Armageddon can safely be ignored, but skepticism is generally a better response than panic.

Next, Joffe asks if there is any country in a position to topple America from its “towering perch,” a perch that is, he shows, far loftier than widely imagined. By contrast, Britain, even at its imperial peak, was merely first among some fairly grand equals. Joffe again buttresses his argument with the wreckage of earlier predictions — that Japan would overtake America, that Europe (Europe!) would fly by, that the Soviets would bury us — before turning a bracingly cold eye on China. The starting point of his enjoyably iconoclastic take on this latest contender is a blend of math and history — “as the baseline goes higher, as economies mature, growth slows” — but it quickly evolves into a perceptive critique of authoritarian modernization (and particularly its Chinese variant) that would make Thomas Friedman very unhappy indeed. Imagining a Chinese Sorpasso any time soon is, maintains Joffe, an extrapolation too far.

What is true of the economic contest is, broadly, true of the military race too. Joffe acknowledges, as he must in the wake of 9/11, “the power of the weak,” but concludes — too sanguine, perhaps, about the equalizing effects of technology — that America is so far ahead of its rivals “that it plays in a league of its own,” and it does so more cannily (“on top, not in control”) and, if not exactly on the cheap, more frugally (amazing, but true, despite those famous Pentagon toilet seats) than the alpha nations that preceded it. America may one day abdicate (Joffe highlights Obama’s combination of “reticence” abroad with “nation-building” at home), but it is unlikely to be imperial overstretch that brings it down.

A drawback of Joffe’s focus on the competition is that it allows relative strength to obscure absolute decay, an error avoided by Alan Simpson when the former senator compared the fiscal condition of the U.S. with that of some European nations. America was, he said, the “healthiest horse in the glue factory,” an ugly truth not inconsistent with the broader observation by Joffe (who, we should note, also frets about deficits) that “only the United States can bring down the United States.”

But an even more profound menace to this country’s future may come from a transformation that owes little to foreign plotting or domestic excess and quite a bit to free trade, free enterprise, and technological progress, features — rightly applauded by Joffe — of the American system that have done so much to make the country what it is today. That America’s generosity and optimism, in the form of an immigration policy — nuttily cheered on by a Joffe still in thrall to ancient Ellis Island myth — may make things even worse only sharpens the irony still further.

The exceptional nation has undeniably been exceptionally successful. Yes, America is an idea and a dream and all that, but above all, it has worked. As Joffe recounts, there have been busts, panics, and slumps, but overall this has truly been a land of opportunity. The result has been a nation held together in no small part by the shared belief that a better life is there for the taking by those who work hard, a belief fed by the fact that it was true enough for enough people for enough of the time, a belief that may now be becoming a delusion.

Inflation-adjusted household median income has yet to return to its 1999 peak — 14 years ago, in case anyone is counting — and now stands at only a fraction more than the level a decade before that, a stagnation that cannot (despite some wishful thinking to the contrary) be explained away by changes in household size. It is no coincidence that the percentage of Americans in work also peaked around the turn of the century, before going into a decline that the Great Recession has only intensified: Work-force participation is back to levels last seen in the disco era, a regression with ominous ramifications for the sustainability of Social Security, Medicare, and all the rest.

The tentative nature of the current recovery, and its particular shape — hiring at the top and bottom of the wage scale has picked up, in the middle not so much — looks a lot like yet more evidence that happy days will not be here again for the American middle class anytime soon. Its labor is simply not as valuable as it was. As technology gets ever smarter, and as workers in lower-cost emerging markets upgrade their skills, opportunities will narrow in the office suite as well as on the factory floor, squeezing cleverer, well-educated Americans of a type who have only rarely been squeezed before. And they won’t like it one bit.

In his fascinating and, in its implications, terrifying new book, Average Is Over, economist Tyler Cowen surveys this scene and predicts the arrival of a “hyper-meritocracy” in which a comparatively small segment (maybe 10 to 15 percent) of the population does extremely well, most people eke their way along, and there are few in the middle: a vision that may be exaggerated, but not by enough to save what’s left of Bedford Falls.

Unlike many apocalypticians, Cowen has room for a little relief (of sorts). He accepts that there will be “some outbursts of trouble” but anticipates a future that is “downright orderly.” The country will be older, and shared pride in America’s leading position in the world (Joffe would not disagree) will throw additional social cement into the mix, while “cheap fun” distracts the potentially restless.