American Icon

National Review Online, October 15, 2001

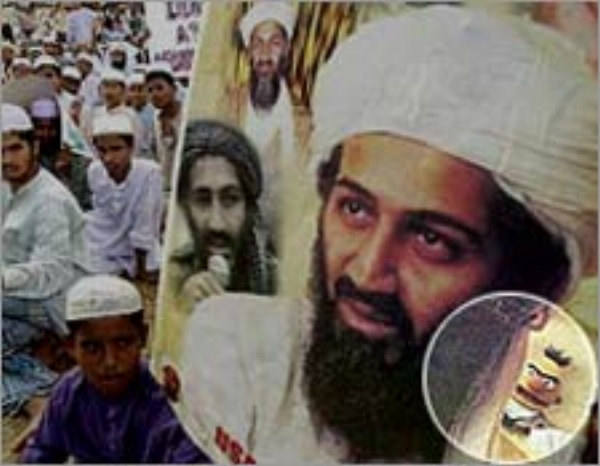

It was a moment of laughter in a month of murder, the return of harmless absurdity to a world gone mad. The background was not promising. Bangladeshi Osamaniacs had gathered in their capital city, Dhaka, to show their support for bin Laden and their hatred for you and me. They marched as such mobs always do, violently, noisily, and under the banners of jihad, an embarrassment, I hope, to their faith and a disgrace, I know, to their country. Posters were brandished, some of them showing pictures of the crowd's hero, that grim symbol of Islamic rage, severe in his white turban and dark beard, with, it was to turn out, a rather surprising companion. Clearly visible on some of the posters, muttering, it would appear, into bin Laden's left ear, is Bert, Sesame Street's grouchiest Muppet, a difficult fellow, to be sure, but not an individual with any previously known links to the al Qaeda network.

Pictures of the demonstration swept across the planet, prompting Fox News to run a piece on "Bin Laden's felt-skinned henchman" and the makers of Sesame Street to issue a rather pompous condemnation of the "abuse" of one of their characters ("Sesame Street has always stood for mutual respect and understanding…this is not at all humorous"), although, as a suspicious Fox correspondent was quick to note, the show's spokeswoman would not be drawn on the yellow Muppet's "current whereabouts." Was there something to hide?

Well, don't worry, Bert, as it happens, is innocent. The real explanation for his appearance with the world's most notorious criminal (which can be found on the invaluable www.snopes2.com) lies elsewhere, in that blend of frivolity and technological superiority that so enrages Muslim fundamentalists about our glittering, tantalizing, ubiquitous civilization. For years now the web has played host to the running joke that "evil Bert" has been the crony and adviser of history's wrongdoers. Search the Internet and you can find doctored photographs of Bert with O. J., Hitler, Kevin Costner (some people really did not like Waterworld) and now, it seems, Osama bin Laden. And this — this joke — was the image that a printer in Bangladesh chose to download when he was surfing the web for a picture of Bin Laden to make into a poster for Osama's devotees. Somehow or other the bungling Bangladeshi either failed to notice Bert or, if he did, he omitted to crop him from the photo.

Symbolically, this fiasco could really not be better: whether it was in the reliance on advanced Western technology to create the propaganda materials for protesters who would abolish the future, or whether it was in the pathetic failure to use it effectively, a failure that led to the elevation of yet another symbol of the decadent West over the heads of its ignorant, benighted foes. It may have been an accidental triumph, but who cares? Western culture, represented in this case by the unlikely standard-bearer, Evil Bert, had once again humiliated its dim, dismal, and demented opponents, fools who would run a world, but cannot operate a PC.

And yes, it is okay to laugh, although if you are a woman in Afghanistan please do so only in private (the Taliban have made it a crime for women to laugh in public). This tale of botched posters is marvelously, gloriously funny, a welcome relief after these weeks of grief. Those demonstrators were made to look ridiculous, and it gave this country a wonderful, mocking picture of a contemptible enemy. We need more of such images. The pampered rich kid bin Laden, a designer tribesman with his laundered robes, Timex Ironman Triathlon ("the watch of choice for top athletes"), and Stone Age certainties is a gift to caricaturists, and yet (with some exceptions, notably The Onion) there seems to be a curious reluctance to make fun of this ludicrous figure. In part, probably, this is a consequence of the exquisite sensitivities of the Politically Correct era (should we not be trying some "mutual respect," should we not be making an effort to understand him?) and in part it is the natural inclination of a sheltered, rather soft generation still uncertain as to how to respond in the aftermath of such an appalling, unexpected onslaught. To take one example, according to press reports, we are, apparently, in for a kinder, gentler Halloween. Bin Laden masks, it is being suggested, would be in poor taste.

In fact, such rude, tasteless gestures are very important, and, insofar as they can contribute to victory, they can help honor our dead. It is possible to belittle bin Laden (in fact, if some tabloid accounts are to be believed, it is very easy indeed), without belittling his crimes. Far from trivializing a conflict, humor can be a very useful weapon in its pursuit. Current reports linking the anthrax attacks on the tabloid press to their less-than-flattering descriptions of bin Laden and his acolytes would, if true, suggest that this is well understood by al Qaeda. Laughing at an enemy boosts morale and reminds us that any adversary, however fearsome-seeming, can be overcome. In the Second World War, Hitler was often portrayed in Anglo-American popular culture as a figure of fun, a laughable, histrionic little man with delusions of grandeur, and yet no one would argue that the Allies were not serious about the evil done by his regime or the importance of, to use a currently fashionable term, 'ending' the Third Reich.

So let's have those bin Laden masks, the nastier the better, and take it from there. This is someone to jeer and to scoff at, a clown in a cave to be mocked, parodied, derided, lampooned, taunted, and ridiculed, a jerk on a jihad that we can only despise. Our laughter will help cheer us up, and, who knows, so great is the reach of the Western media (ask Evil Bert), it may also transmit a message to some of those in the Muslim world who now demonstrate their support for terror, an important message about the man that they so admire.

He's a loser.