Conspiracies So Immense . . .

National Review, December 3, 2007

To talk to Yuri Felshtinsky is to revisit an era meant to have ended when Boris Yeltsin leapt onto a tank in Moscow. But when Dr. Felshtinsky examines photographs of that heroic August day, he sees something else. Visible just behind the Russian leader is Alexander Korzhakov (he’s the balding man in a gray suit), the bodyguard who later became chief of Yeltsin’s Presidential Security Service. “KGB,” notes Felshtinsky. So he had been.

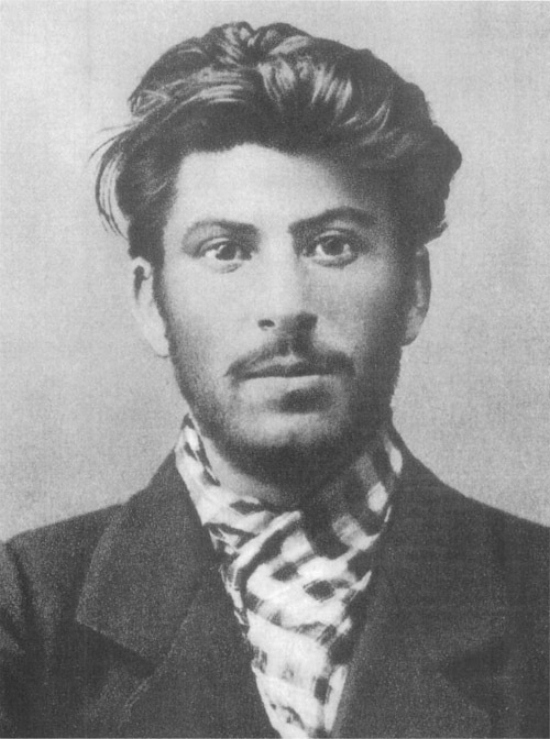

Something similar could have been observed in St. Petersburg. The city’s mayor was a prominent opponent of the hardliners’ coup — but take a closer look at shots of his entourage, and whom do you see? Vladimir Putin, that’s who. “KGB,” says Felshtinsky. And then he smiles.

Felshtinsky is an historian, Russian-born (but now an American citizen), a graduate of Brandeis, a Ph.D. from Rutgers, and connecting the dots is what historians do. But the animated, intense, and likeable Dr. Felshtinsky doesn’t just enjoy his connections and his dots, he treasures them, and when they begin to reveal the outline of something hidden, something mysterious, something denied, ah well . . .

He is quick to regale me with fascinating tales of murder, attempted murder, and conspiracy from the Soviet epoch, tales that have, shall we say, passed most history books by. But before dismissing them all as fantasy, bear in mind that konspiratsia has been a malign feature of Russian politics since the czar’s Okhrana began its elaborate games of deception with the revolutionaries over a century ago. These were games that, in essence, continued, unchanged but for the players, into Soviet times, and if Yuri Felshtinsky is to be believed, they still do. And maybe he should be. In Russia it’s only cranks that have faith in lone gunmen. In a nation with no agreed narrative of past or present, who is to judge where paranoia ends and history begins?

This place of shadows, contradiction, and lies is where Felshtinsky and a former intelligence officer named Alexander Litvinenko researched their book, Blowing Up Russia. Since it was first published in 2002, Litvinenko has been murdered — poisoned in London last year with radioactive polonium-210 — and the book itself has been banned in Russia. The latter can’t have been a shock: Blowing Up Russia may resemble a somewhat discursive academic treatise, but it is as disturbing as it is dry. It is either a monstrous libel or a horrifying revelation. Neither would be acceptable to the Kremlin.

That’s because the book revolves around the allegation that the devastating bombings in Moscow, Buinaksk, and Volgodonsk in September 1999 were the work not, as is usually assumed, of Chechen terrorists, but of elements within the FSB, the principal successor organization to the KGB. The bombings were, it is claimed, what the Soviets would once have called a “provocation” — a provocation of which, Felshtinsky tells me, choosing his words delicately, Putin was “aware.” According to this thesis, they were designed to provide a justification for a fresh attack on Chechnya and, with that renewed war, a political climate that would favor the election to the presidency of Putin, who had recently quit his job as head of the FSB to become prime minister and Yeltsin’s latest presumed successor. If that was indeed the plan, it worked. Russian troops reentered Chechnya in force, Yeltsin resigned in December, and in March 2000 Putin swept into the presidency.

Putin has described such allegations as “madness.” Even to consider them is “immoral,” an argument with some resonance, especially after the emergence of “Truthers” and other conspiracy theorists intent on proving what “really” happened on 9/11. Making matters muddier still, Litvinenko subsequently ruined his own credibility with a series of increasingly far-fetched tales of Putin’s wrongdoing. Felshtinsky explains this by describing his co-author as an “extremist,” a man on a mission, more interested in discrediting Putin than in the truth of the stories he was peddling.

Felshtinsky had doubts about Litvinenko from early on. For all the cooperation between the two men (including Felshtinsky’s role in Litvinenko’s escape from Russia), he leaves the clear impression that they were never particularly close: “We were not friends.” Litvinenko was former KGB/FSB: Such people, asserts Felshtinsky, can never be trusted. Felshtinsky was, he says, insistent that Litvinenko’s contributions to Blowing Up Russia were carefully checked and, where possible, backed up by documentation. He was “professionally tough” with Litvinenko: “I am a historian.”

But he’s been more than that. In 1998, he recounts, he returned to his native country to “somehow move . . . myself from history to politics.” That led him to Boris Berezovsky (then the leading oligarch, then still in Russia, and then thought by many to be the power in the land), and, through him, to Litvinenko. Felshtinsky now reckons that Berezovsky’s power was, in no small part, illusion (“a legend”), that it was really only effective when exercised on behalf of those in charge of the state. That argument may well be an exaggeration, and its logic is more than a touch circular, but it is true that it didn’t take too long before Berezovsky, an early supporter of Putin (Felshtinsky questions how important that support really was), was forced to flee. This left him as one of Putin’s fiercest — and with his billions, most formidable — opponents. Spreading the word that Putin, or his allies, had something to do with the 1999 bombings was obviously in his interest, and so, therefore, was backing the project that became Blowing Up Russia. And that is what he has done.

Litvinenko was financially supported by Berezovsky for a number of years, something that, Felshtinsky says, ended only shortly before his murder. As for his own past and present arrangements with Berezovsky, Felshtinsky is reluctant to discuss them in much detail. There is, however, a vague, and vaguely patronizing, description included by Alex Goldfarb, another Berezovsky acolyte, in his account (co-written with Litvinenko’s widow) of this saga: “In the late 1990s [Felshtinsky] became a peripheral planet in Boris’ solar system, orbiting once every few months, advising him on various matters.”

The Berezovsky camp may have been busy throwing mud at the Kremlin, but the Russian authorities have hit back hard. They have accused the oligarch, a man with a record murky even by the standards of the Yeltsin years, of involvement with Chechen terrorism (he denies the charge), and many other crimes. Allegations have also surfaced that it was Berezovsky who was responsible for arranging Litvinenko’s death in order to embarrass Putin. If there ever has been an example of konspiratsia too baroque to be believed, this is it. That doesn’t alter the awkward fact, a gift to the obsessive, that Andrei Lugovoy, the former KGB/FSB operative now charged by the British with Litvinenko’s murder, once worked in a senior role for Berezovsky and continued to have some degree of access to him even into 2006.

None of these issues, however, nor the questions they raise, is enough in itself to discredit Blowing Up Russia. Its authors make a strong case (albeit one for the prosecution) and they were (and are) not alone in their suspicions. The fates of three prominent individuals who had come to very similar conclusions are, to say the least, suggestive. There was Sergei Yushenkov, an MP for the Berezovsky-backed Liberal Russia party. He called for an investigation into what happened in that summer of 1999. He was gunned down in 2003. Not long afterward, the journalist and opposition MP Yuri Shchekochikhin, who had arranged for extracts from Blowing Up Russia to be published in Novaya Gazeta, one of Russia’s last remaining independent newspapers, died of an “allergic reaction.” In early 2004, presidential candidate Ivan Rybkin described the bombings as a “crime committed by the security agencies.” He later withdrew from the race after having been poisoned (it appears) by psychotropic drugs.

Felshtinsky regards both the Litvinenko murder and the September bombings as evidence of a wider trend: What counts in Russia now is what the FSB wants. In Soviet times, the security services were powerful, but those who ran them were creatures of the state they policed. Everything they had (in reality rarely that much) could be taken from them on a bureaucratic whim. By contrast, the new Russia offers them the chance of becoming, and staying, rich. It’s a chance they have taken. In Felshtinsky’s opinion, Russia has been reduced to little more than a corporate asset, and the shareholders in the corporation that controls it are, primarily, past and present members of the security services.

It’s a corporation where the shareholders will, Felshtinsky believes, feel (and be) threatened if any one of their number becomes too powerful. Thus, he thinks that Putin will soon be made to give up much of his authority. That’s an assumption that is likely to be severely battered in the next month or so. Felshtinsky is, I suspect, on more secure ground in claiming that this is a corporation with a very low degree of tolerance for any disloyalty. Alexander Litvinenko, former KGB, former FSB, not only quit the team (basically, argues Felshtinsky, as a result of a power play that backfired), but also joined up with the other side. According to Felshtinsky the consequences were inevitable. Only the polonium was a surprise.

If Felshtinsky is right, Russia’s democracy is dying. That he even could be shows how sick it already is.

++++

Courtesy of C-Span, more Yuri (and me) here.