The Corpse was Dead and Other Stories

Johan Harstad - The Red Handler

Alexander Lernet-Holenia - I Was Jack Mortimer

Caroline Blackwood - The Stepdaughter

Michel Houellebecq - Annihilation

The New Criterion, November 1 2024

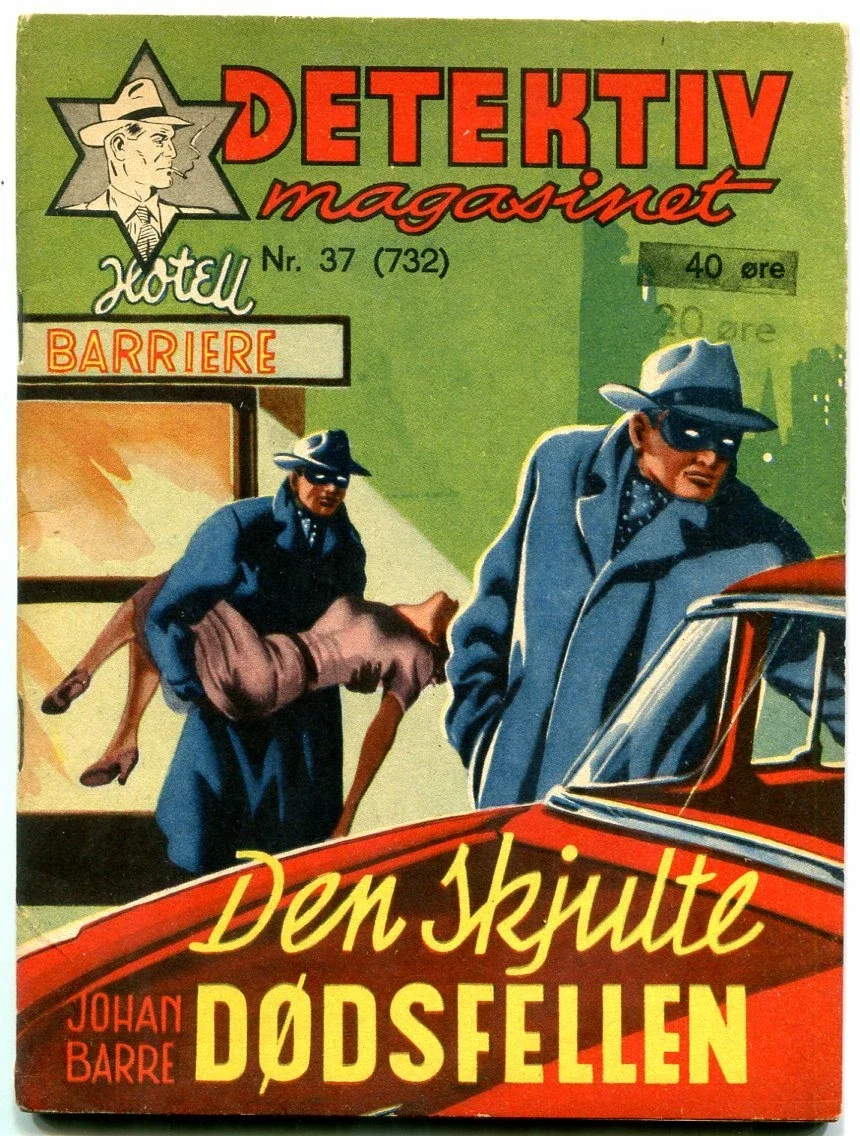

Until gang warfare and the bombings that went with it broke Sweden’s calm (the consequences of recent mass immigration have proved rougher-edged than many Swedes chose to expect), the Nordic region had for a long time been renowned for its tranquility, making it somewhat surprising that it gave birth to Nordic noir, a genre of thriller often as chilly as the realm from which it emerged. Each Nordic country has its leaders in this field, and in Norway the top dog is Jo Nesbø, hip, stylish, something of a polymath (soccer player, stockbroker, musician), and the best-selling Norwegian author of all time, renowned above all for a series of often brutal stories (recommended) featuring Harry Hole, a brilliant, awkward Oslo detective with a fondness for the bottle.

In other words, Nesbø is no Frode Brandeggen (1970–2014), an obscure Norwegian writer of detective stories, who died too (?) young of emaciation in 2014. “Life is short,” he wrote, “but not short enough.” Nevertheless, there’s no sugarcoating starvation: it was a miserable end after an unpromising beginning—his childhood in Stavanger, a city in Norway’s south, was unusually joyless—and a literary career that in his lifetime saw only two works make it into print. The first was a story published in a magazine, the second; released in 1992, was an avant-garde novel, Conglomeratic Breath.

Unfortunately, as another Stavanger-born author, Johan Harstad, explains, due to “its forbidding length and complexity, Conglomeratic Breath was ignored by reviewers and quickly forgotten. It sold poorly,” a generous adverb. Conglomeratic Breath sold at most five copies. Almost all the others were pulped. The editor who toiled on the book for Brandeggen’s publisher, Gyldendal Norsk Forlag (Harstad’s publisher too), left Gyldendal shortly after Conglomeratic Breath was finished. He no longer works in the industry.

“Forbidding length?” Given that one of Harstad’s novels is 976 pages long and another runs to 1,104 pages, a saying about someone living in a glasshus not throwing stones comes to mind. Then again, Conglomeratic Breath was reportedly 2,322 pages long. Brandeggen returned to Stavanger, where his jobs included trash collector and library attendant, but he was dreaming bigger dreams. He was secretly laboring on a new project: devising a way of writing that would enable him to realize his artistic potential, while also appealing to a wider audience. The latter was an objective that was both extremely modest—Conglomeratic Breath could hardly have appealed to a narrower audience—and astoundingly ambitious, given how few concessions Brandeggen had previously made to readability.

These labors led to fifteen novels about a private detective known as the Red Handler. They represented a sharp break from Brandeggen’s earlier logorrhea. Unpublished while Brandeggen was alive, they have now been issued in a single volume titled The Red Handler. Altogether those novels—more accurately, micro-novels—take up no more than 140 pages, and those pages often feature a lot of white space. One chapter of one of the novels comprises one sentence: “this will not do, thought the Red Handler.”

The prose manages to be simultaneously sparse, clumsy, and crammed, a feat of sorts:

The corpse was dead. The Red Handler didn’t even need to check for a pulse to confirm it. His own pulse was pounding furiously. He was in Denmark. That’s how it was in this country. Raw and brutal. He might not get time to kiss his old flame after all.

Brandeggen had, Harstad maintains, been “inspired by the French mouvement artistique du banalisme, which championed anti-climax, cliché, and omission as worthy literary techniques.”

Inquisitive readers won’t find much about banalisme online. What there is, however, is mildly amusing, but irrelevant. Confusingly, the banalism referred in the volume’s second half, a collection of 252 endnotes—an impressive tally for such a sparse text—written by Bruno Aigner, an ancient German, appears to be a seemingly different “movement.” Aigner also claims that his conversations with Brandeggen continued for “three years” after their initial meeting in Dresden in 2013. This is hard to reconcile with Brandeggen’s death in 2014 or, indeed, Aigner’s assertion that he is an annotator of some repute.

But these “errors” are Harstad’s. There was no Brandeggen and there is no Aigner. They are the two main characters in Harstad’s novel, The Red Handler: Collected Works, Annotated Edition (first published in Norwegian in 2018 as Ferskenen, and translated now by David Smith). Ferskenen translates as The Peach, a bewildering title to anyone not knowing that, in Norwegian, Fersken (the second “en” in “Ferskenen” is just “the”) can also mean “red-handed.” Thus han ble tatt på fersken translates as “he was caught red-handed”:

The salesman, not from Microsoft, realized the jig was up. He’d met his match. “Dammit,” he said quietly. “You caught me red-handed. You are too good.”

The Red Handler laughed quietly.

“Just doing my job.”

Brandeggen (as he put it) was writing “crime fiction for the gentleman who loves crime novels, but hates reading.” Chiseling the prose down is a part of that process, but the plot must help too. Catching the criminal red-handed cuts back on the words spent on exposition, a literary practice of which Brandeggen now disapproved, even if, in the view of the exigent Aigner, he still sometimes succumbed to it.

This particular Red Handler novel is wrapped up in three chapters, as is another in which Brandeggen’s preference for red-handed capture comes at the expense of realism. Leaping forth “like a gazelle,” the Red Handler catches a burglar prying open a window, only to be told (by the burglar) that he had leapt too soon, a conclusion that the Red Handler, apparently unaware that attempted burglary is an offense too, accepts.

This reveals a startling ignorance of the criminal law, but the Red Handler has a solution. He tells the thief that he’ll wait. “That was the Red Handler for you,” gloats Brandeggen, “always a step ahead. He smoked a menthol cigarette while the thief went to work.”

Nodding perhaps to Nabokov’s Pale Fire, Harstad tells the tale of the unfortunate Brandeggen through Aigner’s extraordinarily detailed endnotes. In writing these, Aigner has stepped out of his “accustomed shadows,” something he finds “liberating.” These endnotes, like the best of this sadly underrated art form, take on a rich life all their own made even richer by their juxtaposition with Brandeggen’s sparse text.

This may be why Harstad opted for endnotes rather than the more convenient footnotes. Putting Aigner’s occasionally extensive commentary under one of Brandeggen’s anorexic (a tasteless adjective given the cause of the author’s demise, I suppose) sentences would have looked absurd.

Some of the endnotes are themselves annotated, and annotations might come with annotations. Brandeggen was (as am I) a fan of Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine, which, as Aigner relates, boasts a lengthy “apparatus of digressive footnotes, one of which was a several-pages-long footnote about footnotes.” Harstad has written a nonfiction work, Blissard, about the Norwegian band Motorpsycho in the 1990s. More than half the book consists of footnotes.

Not all the notes here are long. Commenting on the first sentence of the second Red Handler novel (“The clouds resembled coagulated blood”), Aigner observes that “Brandeggen was very satisfied” with this opening line. “It was, according to him, ‘quite up to snuff.’”

This strange and funny book is much more than a one-note joke. The best way to see much of it is as a comic dialogue between the Red Handler novels on one side, acting as the straight man, to Aigner, the annotator, on the other. Sometimes Aigner focuses on Brandeggen’s text in a relatively disciplined fashion; sometimes he uses it as a launchpad for depicting aspects of Brandeggen’s ridiculously bleak life.

The Red Handler wouldn’t be properly Norwegian without some gloom. Amid the generally deadpan humor and Aigner’s unreliable unreliability (Cliff Eastwood, the Yugoslav film star, never existed, but William Shatner really did appear in a poorly pronounced Esperanto-language movie), this tale is, at one degree removed, also a depiction of complete psychological collapse. Oh well.

There are some longueurs, particularly when Aigner turns his attention away from Brandeggen or The Red Handler, although his account of trying (and failing: he gives up at page 1,700) to fight his way through Conglomeratic Breath is a miniature masterpiece. The book opens with the protagonist standing on the front steps of his house, fishing around for his keys, and going inside once he finds them:

This takes one hundred fifty pages. From there, it’s full-on disintegration, until our level of disorientation becomes monumental and absolute. . . . But then, somewhere around page 700, the text suddenly arrives at a light in the forest, a clearing. The reader’s relief is enormous, almost indescribable, as Brandeggen gives us an unpretentious affecting account of life on a street in Stavanger in the mid-70s.

But “on page 1,009 the new story abruptly ends and the forest becomes thicker and more impassible than ever.”

The last (and first) book by the Austrian writer Alexander Lernet-Holenia (1897–1976) that I reviewed in these pages (in November 2022) was his haunting, dreamlike Baron Bagge (1936), a novella set in the Carpathians during the First World War, where Lernet-Holenia had served as a cavalry officer. Now I Was Jack Mortimer, an English translation by Ignat Avsey of Lernet-Holenia’s Ich war Jack Mortimer (1933), has been reissued in the United States.

Lernet-Holenia was a conservative of aristocratic descent (or more—there were persistent rumors that his real father was his father’s commanding officer, the Habsburg archduke Karl Stephan, briefly in the running to be a future King of Poland, a decision in which the Poles played little or no part). The sadness over the loss of the old united Mitteleuropa never left Lernet-Holenia, and Baron Bagge looks back to that past. But I Was Jack Mortimer is set in the here and now, where the here is Vienna, and now is the early 1930s:

Right there on the left was a slot-machine bar.

He went in.

It was a large, circular, dome-shaped room with slot machines around the perimeter and tables in the middle at which people were eating and drinking.

A radio was blaring.

He walked past the machines and studied the labels. Over one of the taps was the inscription “Sherry.”

He picked up a glass, held it under the tap, and inserted a coin in the slot.

There are many people who don’t enjoy the luxury of having dessert wines served up elegantly. Slot-machine bars are meant for the likes of them.

We are a long way from the Hofburg.

But although the Vienna of I Was Jack Mortimer is firmly set in its era, traces of the vanished empire still endure. Aristocratic lineage still counts, at least if those with it still have money, as not all of them did. The war had taken a financial as well as a human toll, and the former was compounded in the fighting’s aftermath by the breakup of empire, and hyperinflation. There had been some fiscal recovery, but, by the early 1930s, the economy was again sliding as the Great Depression gathered pace, helped on its way by the collapse of a major Austrian bank, Creditanstalt.

When the novel’s somewhat hapless, if handsome, protagonist, Ferdinand Sponer, a twenty-nine-year-old taxi driver, finally picks up the courage to introduce himself (after some sleuthing to find out who she is) to the beautiful young woman—Marisabelle von Raschitz (a “von,” no less; the niece of a countess, no less), who had been one of his passengers the previous day—he is quick to tell her that he comes from more than taxi driver stock: I even spent a whole year in . . . a cadet school. . . . Actually my father was . . .” She doesn’t seem to care, merely acknowledging the fact and adding that “nowadays all sorts become drivers. That’s just the way it is . . . one just has to . . .”

And no, she doesn’t want a cab.

Marisabelle’s remark stands out in a novel in which there is little direct comment on the tough times Austria was going through, although it is obvious that the life lived by Sponer and others at his level was hardscrabble. In Sponer’s case, it is made more painful still by his awareness of how the war that took his father—and the aftermath that then took away just about everything else—has deprived him of the more comfortable existence that would probably have been his. As for his girlfriend Marie Fiala (a Czech or Slovak name, no “von”), she has lost her job as a shop assistant. She has been unemployed for months, doing odd jobs here and there.

Austria’s politics, bitterly and not infrequently violently divided between left and right, don’t intrude either, even though the early 1930s were a period of constant crisis, including an autogolpe by the country’s chancellor, a diminutive clerico-fascist, in the year that I Was Jack Mortimer appeared. Graham Greene divided his novels into “serious fiction” and “entertainments.” Perhaps Lernet-Holenia did the same. He was a versatile writer, a poet, and a popular playwright as well as a novelist. Maybe he just wanted this book to be fun. With a couple of murders, serial smoking, a grand hotel, punch-ups, chases, wife-stealing, jealous rages, psychopathy, New Mexico (yes, New Mexico), and “Winifred’s thin evening dress [that] immediately tore into shreds,” how could it not be?

Sure enough, within two years, a film based on Ich war Jack Mortimer was made in Germany, despite Lernet-Holenia’s presence on the blacklist that inspired the Third Reich’s early book burnings. The Nazis regarded him with suspicion, as a supporter of a separate Austrian identity and for his mitteleuropäisch cosmopolitanism. A second version of Ich war Jack Mortimer was shot in Austria in 1952, followed by a West German television film a decade later.

Before I Was Jack Mortimer has advanced too far, Sponer has more to worry about than how to woo Marisabelle (or move on from Marie). Marie isn’t pretty, but that wasn’t the problem. She has a good figure and “marvelous blonde hair.” But their relationship was stuck, going nowhere.

Sponer picks up a passenger at the Westbahnhof, who wants to go to the Hotel Bristol. “The Old or the New Bristol?” he asks, with the cab underway. No reply. He looks around. The man is leaning back, “staring impassively out of the window.” He asks again. No reply:

Sponer turned on the interior light and saw him leaning back heavily. His coat was undone and he was clutching his right side with both hands as though looking for something in his pocket. His head was slumped to one side and his mouth was half open.

He remained completely motionless.

The man was dead.

The corpse was dead, eh? Sponer panics. He botches telling the police what has happened, and—not the last of his poor decisions—fearing

that they won’t believe him, decides not to try a second time. Plan B: dump the body in the Danube.

The story tears along at a tremendous pace, so much so that the writing occasionally struggles to keep up. Then again:

Some of the windows in the street were lit dimly from within, and every now and then the pale moonlight fell on the tall chimney stacks and grey walls of the houses, where here and there the stucco had come away in large patches.

The few passers-by paid no heed to Sponer and his car. A cat ran across the street, jumped over the steps and disappeared.

Lady Caroline Blackwood (1931–96) did not appreciate being labeled a muse, but, as a strikingly beautiful woman married in sequence to a painter, a composer, and a poet, she must have known that this was a risk she was running. Her father was a marquess, her mother, dangerously, a Guinness, a tribe with a wild side. Thus she and her siblings were products of the Anglo-Irish ascendancy, brought up—if that’s the right term—in conditions of decaying grandeur in one of Northern Ireland’s largest and leakiest big houses. Their father was often away pursuing his political career, and after 1939 on war work or in the army. He was killed in Burma in 1945. Their mother (she and her sisters, the golden Guinness girls, were “lovely witches,” said John Huston) had other things to do, leaving the children neglected. Some of Blackwood’s oeuvre is described as gothic. It’s not hard to see why.

Blackwood had been writing nonfiction for some years. Her first full-length(ish) venture into fiction, the grim, intense The Stepdaughter, a gem that somehow absorbs light, was published in 1976. It has now been reissued, with a foreword by Heidi Julavits. I had never read anything by Blackwood before, although I had heard her name. She had been in the public eye for a long while, married to Lucian Freud in the 1950s, part of Soho’s self-consciously drunken scene, and on from there.

She was considered to be emotionally cold. According to Christopher Isherwood, she was “only capable of thinking negatively.” Even so, the first half of the first sentence of The Stepdaughter begins cheerfully enough: “For weeks now I have been sitting in my apartment, which has a panoramic view of the splendors . . .” But what follows prompts a swift reassessment: “and squalors of Manhattan, and I have been writing letters in my head.” Replacing “squalors” with the collective “squalor” would understate the extent to which each one drags J, our protagonist, down. In the 1970s, there were many of them in Gotham. Gone forever now, of course. Writing letters in her head (to herself, it turns out) doesn’t sound good. And “for weeks now I have been sitting in my apartment” signals immobility, not relaxation.

But J (as much of a name as she is given) is immobilized, “loll[ing] around all day in her dressing gown.” Left unanswered is the question why, apart from occasional—or maybe not so occasional—moments of paranoia in which she believes she has become a pariah, she no longer leaves the apartment in which she feels trapped. When the chance comes for some company, she resents it. She swallows “fistfuls” of Valium, but it doesn’t deliver the much-needed calm (at the point someone has crossed the fistfuls threshold, that might be too much to hope for)—nothing does. How about a job, J? It’s the Seventies, not the Fifties. That The Stepdaughter takes the form of an epistolary novel in which the letters are only written by one person increases the sense of claustrophobia so skillfully evoked by Blackwood.

J, who is in her mid-thirties, does not live alone in the apartment. Naturally this hell (maybe?) contains other people. There’s her stepdaughter, Renata, thirteen; Monique, the French girl sent to help out by J’s soon-to-be ex-husband Arnold (now decamped to Paris to join his new girlfriend); and J’s four-year-old daughter, Sally Ann. Monique was lured over by the promise of learning English with a New York family, a wholesome-sounding adventure, only to discover that she’s landed in, well, this.

After two months, Monique has learned no English as no one really speaks in the apartment, other than Sally Ann, chattering away in four-year-old. When the lost, bored, frantic Monique . . . tries to communicate with Sally Ann, it’s with the desperation of some prisoner in an ancient dungeon who tries to save his sanity by talking to the rats.

J keeps telling herself she will arrange opportunities for Monique to meet youngsters and fellow French people, but never does. She ought to thank Monique for the excellent meals she cooks, but never does.

It’s Renata who enrages J the most, even if that rage is confined to her thoughts and manifested in “things not done rather than any cruel things performed.” Renata should be Arnold’s burden, not hers. He’s gone but is (so far) paying for a far more expensive apartment for J than he would be obliged to, an unspoken bribe to ensure that Renata is kept away from the father embarrassed to be seen with her.

Renata is fat, unattractive. Her mother is unavailable to assist: she’s a chronic alcoholic who has been institutionalized for psychiatric problems. The same might have been said of Blackwood’s third husband (they were still married, just, at the time), the poet Robert Lowell, except that his institutionalizations were brief. Blackwood, also an alcoholic, borrows a secret from her own entangled past to insert into the plot (it would be too much of a spoiler to reveal it now). In real life, it remained hidden for years yet. Blackwood’s daughter Natalya may well have seen herself in the depiction of Renata, a possibility that Blackwood must have been either oblivious of or indifferent to. Natalya died of a heroin overdose aged seventeen in 1978.

“Renata,” writes Blackwood,

was very tall for her age and so immensely overweight that the matronly spread of her huge body gave her the look of someone prematurely middle-aged.

The insults (again, never spoken aloud) and nasty anecdotes continue. Renata has “poor, thin hair” and “fat-buried features.” She is a “maker of instant cakes,” which she doesn’t share. She doesn’t flush (and that’s not the worst of the bathroom horrors). J’s venom is meant to be overstated, but it goes on a little too long for comfort, suggesting that some of it might be Blackwood’s too.

J is being consumed by her silent rage. She’s lost her appetite, she’s losing her looks and, evidently, also her mind. But her rage is draining others too. Sally Ann “seems to whine all day long.” Monique’s “hair is hanging down in dark greasy strings.” Renata’s “eyes look permanently swollen.”

This won’t end well (it doesn’t).

The French author Michel Houellebecq is best known in this country for Submission (2015), a novel in which a candidate from an Islamic party wins France’s 2022 presidential election (bullet dodged!). Houellebecq is now well into his sixties. There was already something weary, even a touch valedictory about his last book, Serotonin (2019). Now comes Anéantir (2022, published this year in English as Annihilation in a translation by Shaun Whiteside). The acknowledgments at the end conclude: “it’s time for me to stop.”

If Houellebecq abides by that, he’s going out with a sprawl. Annihilation is leisurely and overlong, with overlapping plots that cover a great deal of ground, from French politics to cyberterrorism, to real terrorism, to societal decay, to the importance of family, to the treatment of the elderly, to (for Houellebecq) a surprisingly tender love story, to the handling of the approach of death, and, no less importantly, some of its ghastlier preludes (Houellebecq is fiercely opposed to euthanasia and assisted suicide). As usual with Houellebecq, there is caustic social commentary, some decent jokes, crude talk about sex, and actual sex. Spiritual and philosophical matters are pondered, never a plus for me, but some may find them of interest.

Annihilation is as muddled as it is long. Perhaps, having decided this would be his last novel, Houellebecq thought he would gather up various ideas he had lying around and throw them into the mix. He put in some dreams too. One moment Paul Raison, a senior civil servant and Annihilation’s principal protagonist, is wandering around Lyon after seeing his father, Édouard, who is in a coma after a massive stroke. Suddenly he is on a bus in the American Southwest. A dark-haired individual with a “satanic” face pushes an old man out of the bus into the void. I began to speed-read through the dreams.

The plight of the Raison patriarch brings his family together, not always easily, and also acts as a trigger for the step-by-step reconciliation between Paul and his wife Prudence, who still live under the same roof, but are in no sense together.

Édouard emerges from the coma, if not particularly far. He remains paralyzed and is sent to a care facility. His “companion” Madeleine is allowed to stay to help look after him until the nursing home’s labor union objects: Madeleine is not properly qualified, you see. The ways in which she can assist Édouard are severely reduced. Making matters worse, budget cuts mean that patient care is curtailed: less therapy and fewer baths, with predictably horrible results.

At this point, Annihilation’s narrative shifts again, when activists dedicated to extracting old people from the medical facilities that may kill them agree to rescue Édouard. Their movement was founded by an American businessman from Oregon. “A well-known billionaire?” asks Cécile, another of Édouard’s children. No, a “small billionaire.”

The mission is successful.

Shortly thereafter, Paul visits his father, who spends his day in a wheelchair in the conservatory that had always been his favorite room in his house. From there Édouard can look at the trees. Every so often Madeleine moves his wheelchair to give him a change of view. Paul being Paul (and Houellebecq being Houellebecq), he speculates whether his paralyzed father was still capable of some sort of sex life. If he was, Paul reckons, then, given that he can also read and “contemplate the movement of leaves stirred by the wind . . . then he was lacking absolutely nothing in life,” a questionable proposition best understood by Houellebecq’s attitude toward euthanasia and assisted suicide. To be fair, Paul qualifies it later with as “pleasant a life as possible.” And not everyone sharing Édouard’s fate will have a conservatory, or a Madeleine.

One of Annihilation’s many subplots or main plots (it’s hard to distinguish between them) is a French presidential election in which an (unnamed) Emmanuel Macron is scheming behind the scenes. This portion of the book has been overtaken by events. It is (almost) unimaginable after the humiliation of “Jupiter,” as he is sometimes known, in two sets of elections this year.

But all that is overshadowed by the book’s powerful closing section, in which (Annihilation is too unstructured to worry about spoilers), after what he believes to be a persistent toothache takes him to the dentist, Paul treads a path taken by countless millions before him. The routine checkup reveals something that warrants a second look. As the diagnoses darken, the examinations go deeper, and the machines that carry out those examinations grow larger. One of his doctors “seemed to be a kind of servant of the machine.” Paul has cancer of the jaw.

Paul’s options shrink and become more unpleasant: removal of large parts of the jaw, his chin, his tongue (which can be replaced, but its function will mainly be decorative). He declines, opting instead for chemotherapy, aware that there is scant chance that it will make much difference. He is now

in the midst of the damned, the incurable, in a community that would never be one, a mute community of beings gradually dissolving around one.

His only real comfort is Prudence, whose is comforted in turn by her belief in reincarnation, a product of a religious odyssey that has taken her to Wicca.

When choosing what to read while receiving his treatment, Paul rejects Pascal and opts for Sherlock Holmes. Good choice. Conan Doyle, writer, doctor, and spiritualist, would, at several levels, have been delighted.