Resistance Is Futile

The Weekly Standard, December 28, 2009

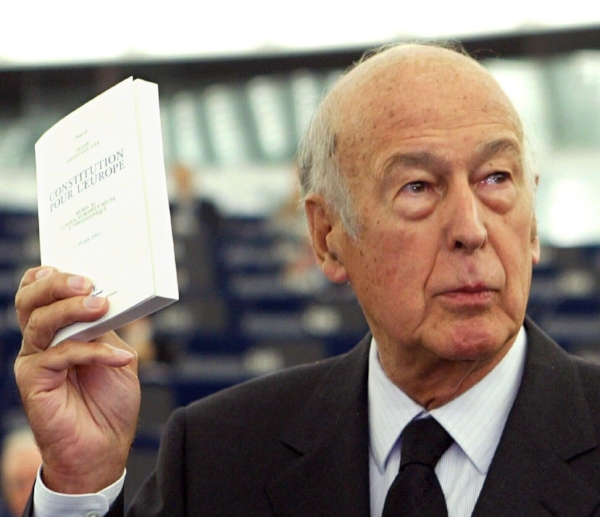

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive--at least if you were Valéry Marie René Georges Giscard d'Estaing. The one-term president of France was awarded the job in 2002 of chairing the convention responsible for designing a constitution for the European Union. He compared his fellow delegates--a dismal, handpicked, largely Eurofederalist claque--with America's Founding Fathers, and, splendidly de haut en bas (however tongue-in-cheek), told this self-important rabble that, in the "villages" they came from, statues would be put up in their honor--"on horseback" no less.

But that's not quite how it worked out. When the villagers saw the hideous blend of bureaucratic centralism, transnational control, political correctness, and daft pomposity that slithered out of Giscard's convention, they were none too impressed. The draft constitution staggered its way to approval in some EU countries, but was killed off by referenda in France and Holland in mid-2005.

Except that's not quite how it worked out. Properly speaking, those two defeats should have put a stake through the heart of the constitution. Instead the ratification process was frozen "for a period of reflection"--a dignified term for buying time to cook up a scheme to bypass the awkwardness of voter disapproval. The scheme was the Treaty of Lisbon.

It preserved the content of the draft constitution, but junked its form. The constitution that had been rejected was scrapped, but its essence was preserved under the guise of a series of amendments to the EU's existing treaties that smuggled in most of the changes which would once have been incorporated in Giscard's monstrosity. It was a stroke of genius. Dropping the "c" word minimized the legal or political risk that referenda might once again be required. It was also an insult. Neither Giscard nor the key architect of the new treaty, Germany's chancellor Angela Merkel, made any attempt to conceal their view that the substance of the constitution was alive and well.

Channeling Louis XIV, Nicolas Sarkozy ruled that France's disobedient voters would be denied any further say on the matter. No surprise there, but I like to think that Merkel's coup might have caused a few pangs in the ranks of Holland's rather more respectable Council of State (the government's highest advisory body). Maybe it did, but the august if pliable Dutchmen somehow felt able to determine that the new treaty did not contain enough "constitutional" elements to require a referendum. Meanwhile, Britain's shameless Labour government just brazened things out. Labour had been reelected in 2005 on the back of a manifesto that included the promise of a referendum should the United Kingdom be asked to sign up for a revived constitution. The Lisbon Treaty was, however, cooed Messrs Blair and Brown, something completely different. There would be no popular vote.

In Ireland, though, significant changes to the EU's treaties require a constitutional amendment, and the Irish constitution can only be amended by referendum. The Irish government did not attempt to dodge its responsibilities. Nor did Irish voters. In June 2008, the Lisbon Treaty was voted down. As the treaty had to be ratified in each of the EU's 27 member states, the Irish snub should have finished it off. Except (you will be unsurprised to know) that's not quite how it worked out.

Within minutes of the Irish vote, the EU's top bureaucrat, Commission president José Barroso, announced that the treaty was not dead. When it comes to the European project, no does not mean no--as Danish and Irish voters had already discovered in the aftermath of their rejection of earlier EU treaties. Ratifications of Lisbon rolled in from elsewhere, the Irish government secured some placatory legal guarantees, setting the stage for a mulligan this October. In the event, however, the result of this second vote was determined not by the changes won by the Dublin government, but by the global financial meltdown, a blow that had brought Ireland's over-leveraged economy to its knees.

There was something almost refreshing in the lack of subtlety with which Barroso traveled to Limerick to announce--just weeks before the second referendum--that Brussels (in other words, the EU's conscripted taxpayers) would be spending 14.8 million euros to help workers at Dell's Irish plant find new jobs. In case anyone missed the point, Barroso also reminded his listeners that the European Central Bank had lent over 120 billion euros to the battered Irish banking system. Frazzled by financial disaster and fearful of the consequences of alienating their paymasters, Ireland's voters reversed their rejection of the Lisbon Treaty just a couple of weeks later.

Being a realist means knowing when to fold. In the wake of the Irish vote, a nose-holding, teeth-gritting Polish president committed his country to the treaty. This left the Czech Republic's profoundly Euroskeptic president, Václav Klaus, as the last holdout. If Klaus could delay signing the treaty (which had, awkwardly for him, already been approved by the Czech parliament) until after a likely Conservative victory in the upcoming British general election (due no later than next June), then the whole process could be brought to a halt. The Tories had vowed to withdraw the U.K.'s existing ratification and hold a referendum on the Lisbon Treaty before proceeding any further. Given most Britons' views (quite unprintable in a respectable publication), the result would have been to kill the treaty. The U.K. isn't Ireland. The U.K. isn't Denmark.

If, if, if . . .

It didn't take long for the blunt Klaus to dash those hopes: "The train carrying the treaty is going so fast and it's [gone] so far that it can't be stopped or returned, no matter how much some of us would want that."

Klaus signed the treaty on November 3. Shortly thereafter the EU's leaders began maneuvering to fill two new jobs: "president" (actually president of the European Council) and "foreign minister" (the latter will rejoice in the grandiloquent title of High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy). Following a couple of weeks of intrigue, backstabbing, and secretive quid pro quos, it was agreed the new president would be Herman van Rompuy--Belgium's prime minister and thus a man who knows a thing or two about unnatural unions. But the somewhat obscure van Rompuy (what Belgian prime minister is not?) is a world historical figure when compared with the woman who has become High Representative, a Brit by the name of Baroness Ashton of Upholland, a dull hack known--if at all--for her loyalty to the Labour party. The treaty finally came into force on December 1. The age of van Rompuy had begun.

Some commentators are presenting the emergence of the Belgian and the baroness as a triumph for the EU's member states over its bureaucracy's more federalist vision. The thinking goes that by securing the appointment of two nonentities to what are (notionally) the most prestigious jobs in the union's new structure, Sarkozy, Merkel, and the rest of the gang successfully defended what remains of their countries' prerogative to decide the most important matters for themselves. To believe this is to misread just how lose-lose the situation was. In reality, the nonentities will be as damaging (maybe even more so) to what's left of national sovereignty as better-known candidates such as the much-anticipated Tony Blair. Blair would have given the presidency more clout. He would have done so, however, at the expense not only of the EU's member states, but also of the Brussels bureaucracy.

The EU's new president is, as mentioned above, technically the president of the European Council, a body formally incorporated within the EU's architecture by the Lisbon Treaty after years in a curious organizational limbo. With a membership now made up of the union's heads of government, van Rompuy, and the inevitable Barroso, it is theoretically the bloc's supreme political institution. And theoretically therefore, the stronger it is (and with a heavyweight president it would supposedly have been stronger), the more it would be able to operate as a counterweight to the bureaucrats of the EU Commission. I suspect that this would never have been the case, but with van Rompuy, a housetrained federalist (he has already told a meeting arranged by--let a hundred conspiracy theories flower--the Bilderberg Group that he favors giving the EU tax-raising powers), at its helm, the point is moot. The key, van Rompuy reportedly claimed, to high office within the EU is to be a "gray mouse," and so, to the chagrin of Blair and those like him, it has proved. Sarkozy, Merkel, and all the rest of their more colorful kind will continue to prance and to parade, and power will continue to leach away from the nation states and into the unaccountable oligarchy that is "Brussels."

"It's all over," my friend Hans told me when Klaus threw in the towel, "Brussels has won." Hans, thirtysomething, a native of one of the EU's smaller nations, and a former adviser to one of the continent's better-known Euroskeptics, comes as close to anyone I have ever met from the European mainland to being a Burkean Tory--and Hans has now given up. He would, he sighed, have to move on with his life.

With Lisbon in force, little is left of the already sharply curtailed ability of any one member-state (or its voters) to veto the inroads of fresh EU legislation. In Hans's view, the treaty means that the momentum towards a European super-state is now irreversible. With their sovereignty emasculated and, in many cases, their sense of identity crumbling under the linked assaults of multiculturalism and mass immigration, the old nation states of Europe have neither the ability nor the inclination to say no. Euroskepticism will now be portrayed (not always inaccurately) as the mark of the crank or the Quixote. "And that," added Hans, a man still at a relatively early stage in his career, "is not the way to go either politically or professionally."

Signing up, however unenthusiastically, for the orthodoxies of the European Union is now de rigueur in the continent's ruling class. And if there was once idealism behind the Brussels project it has long since been overwhelmed by another of the beliefs that lay behind it--that neither nations nor their electorates could be trusted to do the right thing. Sovereignty, whether national or democratic or both, is being replaced by oligarchy, technocracy, and the pieties of the "social market." If you live in an oligarchy, it's best to be an oligarch.

This realization is one of the reasons that the EU has got as far as it has. It has provided excellent opportunities for some of Europe's best, brightest, and lightest-fingered to move back and forth between the union's hierarchy and those parts of the private sector (and indeed the national civil services) that feed off it.

Yet all was not gloom, said Hans. A stronger sense of their own identity and a still distinct political culture meant, he thought, that it wasn't too late for the Brits to do the right thing (as he sees it) and quit the EU. He is too optimistic. While correct that most Britons are irritated by the EU and its presumptions, he overlooks the fact that they have not yet shown any signs of wanting to end this most miserable of marriages. Hans also underestimates the subtler factors standing in the way of the long-promised punch-up between any incoming Tory government and Brussels--an event that in any case has now been postponed. David Cameron's party has shelved its plans for a referendum on the Lisbon Treaty. Now that it has come into force, modifying the treaty to accommodate the U.K. would require the assent of all the other member-states and that won't be forthcoming. A British referendum, Cameron claims, would therefore be pointless. How convenient for him.

Cameron has also made it clear that he has no intention of revisiting the U.K.'s relations with the EU in any serious way for quite some time. With Britain's economy in ruins, any incoming government will have more pressing priorities. And the passing of time only further entrenches the EU's new constitutional settlement deeper into the U.K.'s fabric--and especially the landscape in which the country's able and ambitious build their careers. That's something that Cameron may also have recognized. He appears to have concluded that it is better to win a premiership diminished by Brussels than no premiership at all, and a major row over Britain's role within the EU could yet cost the Tory leader the keys to 10 Downing Street.

The additional complication is debt-burdened Britain's dependence on the financial markets as a source of fresh funds. Investors are averse to uncertainty. They are already twitchy about Britain's disintegrating balance sheet, and a savage row between Britain and the rest of the EU would set nerves even further on edge. Then there's the small matter that such a conflict is hardly likely to help Britain persuade its European partners to bail the U.K. out in the event that this should prove necessary--and it might.

The more time passes, the more an empowered EU will insinuate itself within national life (rule from Brussels is a fairly subtle form of foreign occupation: No panzers will trundle down Whitehall). It will come to be seen as "normal," not perfect, by any means, and certainly the cause of sporadic outbreaks of grumbling, but if handled with enough discretion (it will be a while before the Commission resumes efforts to sign Britain up for the "borderless" EU of the Schengen Agreement) and enough dishonesty, it will benefit from the traditional British reluctance to make a fuss. As on the continent, protesting deeper integration within the union, let alone trying to reverse it, will be depicted--and regarded--as the preserve of the eccentric and the obsessive.

With Britain hogtied, the Lisbon structure will endure unchanged unless a prolonged economic slowdown (or worse) finally shatters the gimcrack foundations on which the EU rests. That cannot be ruled out, but if Lisbon holds, the implications will be profound for the international environment in which the United States has to operate. There is already chatter (from the Italian foreign minister, for instance) about a European army. Can it be long before there is a drive by Brussels to replace the British and French seats on the U.N. Security Council with one that represents the entire EU, a move that would eliminate the one vote in that body on which the United States has almost always been able to rely?

And to ask that question is to wonder what sort of partner the EU will be for the United States. One clue can be found in the fact that the new High representative for foreign affairs and security policy was treasurer and then a vice chairman of Britain's unilateralist Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament at the end of the Brezhnev era. Another comes from remarks by Austria's Social Democratic chancellor Werner Faymann in response to the speculation that Tony Blair would be appointed to the new presidency during the fall: "The candidate . . . should have an especially good -relationship with Obama and not stand for a good working relationship with Bush."

Leaving aside the minor matter that George W. Bush has not been president for nearly a year, it's not difficult to get Faymann's drift. The Obama administration will find the EU a reasonably congenial partner, even ally, so long as it sticks to the sort of transnationalist agenda that could have been cooked up in Turtle Bay, the Berlaymont, or Al Gore's fevered imagination. If on the other hand, Obama, or any subsequent president, should turn to policies that are more avowedly in this country's national interest, the EU could well turn out to be an obstacle. After all, in the absence of any authentic EU identity, its leadership has often defined their union by what it is not. And what it is not, Eurocrats stress, is America.

Washington will have to learn to accept surly neutrality, if not active antagonism, from the oligarchs of Brussels. The EU may not be able to do much to hinder the United States directly, but, as its "common" foreign (and, increasingly, defense) policy develops, there's a clear risk that it will be at the expense of NATO. Shared EU projects will drain both cohesion and resources away from the Atlantic alliance, not to speak of the ability of America's closer European allies to go it alone and help Uncle Sam out.

Some of this will be deliberate, but more often than not it will be the result of institutional paralysis. As a profoundly artificial construction, the EU lacks--beyond the shared prejudices of some of its elite--any sense of the idea of us and them that lies at the root of a nation or even an empire, and, therefore, the ability to shape a foreign policy acceptable to enough of its constituent parts for it to take any form of effective action. But if the EU might find it difficult to decide what it will do, it will find it easy to agree what its members cannot do. The days when Britain will have the right, let alone the ability, to send its troops to aid America over the protests of Germany and France are coming to a close.

Bowing, but this time to the inevitable, Obama has welcomed the completion of the Lisbon Treaty process, saying that "a strengthened and renewed EU will be an even better transatlantic partner with the United States," an absurd claim that one can only hope he does not believe.

Ah yes, hope.