Constitutionally Indisposed

National Review Online, February 22, 2005

A little over two centuries ago, a small group of planters, landowners, merchants, and lawyers met in Philadelphia to decide how their new country was to be run. Within four months this remarkable collection of patriots, veterans, pragmatists, geniuses, oddballs and the inspired succeeded in agreeing the extraordinary, beautiful document that, even with its flaws, was to form the basis of the most successful nation in history.

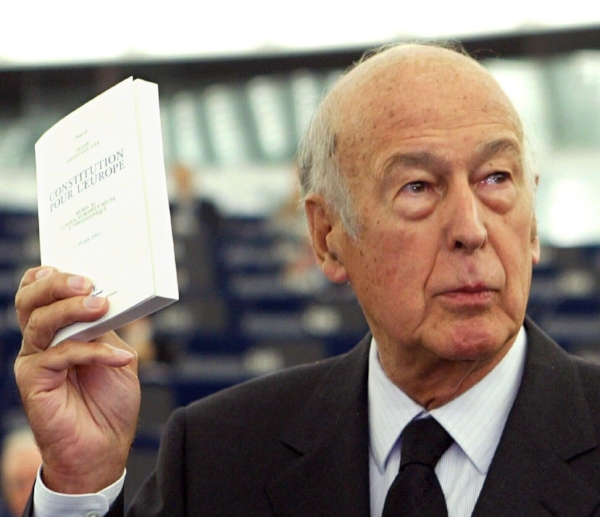

On February 28, 2002, another constitutional convention began its work, in Brussels this time, not Philadelphia. Its task was to draw up a constitution for the European Union. The gathering in Brussels was chaired by Giscard D'Estaing, no Hamilton or Madison, but a failed, one-term president of France best known for his unseemly involvement with Jean-Bedel Bokassa, the cannibal "emperor" of central Africa. Giscard's convention was packed with placemen, cronies, creeps, and has-beens to make up a body where to be called second rate would have been an act of grotesque flattery. Only a fool, a braggart, or a madman would have compared this rabble with the gathering in Philadelphia. Needless to say, Giscard managed to do just that. The rabble returned the compliment. At ceremonies held to celebrate the conclusion of the convention's work, one over-excited Austrian delegate compared Giscard to Socrates, a remark that would undoubtedly have reduced that ancient, and unfortunate, Greek to yet another swig of hemlock.

Once the convention had completed the draft constitution, there was further haggling over the text by the governments of the EU member states. A final version was agreed in June 2004, and what a sorry, shabby work it is, an unreadable mish-mash of political correctness, micromanagement, bureaucratic jargon, artful ambiguity, deliberate obscurity, and stunning banality that somehow limps its way through some 500 pages with highlights that include "guaranteeing" (Article II-74) a right to "vocational and continuing training," "respect" (Article II-85) for the "rights of the elderly... to participate in social and cultural life," and the information (Article III-121) that "animals are sentient beings." On the status of spiders, beetles, and lice there is, unusually, only silence.

All that now remains is for this tawdry ragbag to be ratified in each member state, a process that is already well underway. In some countries ratification will depend on a parliamentary vote, in others a referendum. The final outcome remains difficult to predict, and it is a measure of the current uncertainty over the constitution's ultimate fate that there is now open discussion of the idea that the document may be forced through even without ratification by one or two of the smaller countries. In an editorial over the weekend, the Financial Times, a generally reliable mouthpiece for the latest Brussels's orthodoxy explained, "in theory, one state's rejection is enough to kill [the constitution]. In practice, it will depend on the state." Within the EU, it seems, some nations are more equal than others. Rejection by one of the union's larger members, however, will be enough to throw the whole process into richly deserved chaos. We can only hope.

And it is at this point that, rather surprisingly, the Bush administration has come into the picture. Speaking a few days ago to the Financial Times, Condoleezza Rice appeared, weirdly, to give the constitution some form of endorsement: "As Europe unifies further and has a common foreign policy—I understand what is going to happen with the constitution and that there will be unification, in effect, under a foreign minister—I think that also will be a very good development. We have to keep reminding everybody that there is not any conflict between a European identity and a transatlantic identity..."

In a later interview with the Daily Telegraph, President Bush himself appeared to steer discussion away from the proposed constitution, but he did have this to say: "I have always been fascinated to see how the British culture and the French culture and the sovereignty of nations can be integrated into a larger whole in a modern era," he said. "And progress is being made and I am hopeful it works because one should not fear a strong partner."

How can I put this nicely? Well, there is no way to put it nicely. Even allowing for the necessity to come out with diplomatically ingratiating remarks ahead of a major presidential visit to the EU, the comments from Bush and Rice are either delightfully insincere or dismayingly naïve.

The project of a federal EU has long been driven, at least in part, by a profound, and remarkably virulent anti-Americanism, with deep roots in Vichy-era disdain for the sinister "Anglo-Saxons" and their supposedly greedy and degenerate culture. Throw in the poisonous legacy of soixante-huitard radicalism, then add Europe's traditional suspicion of the free market, and it's easy to see how relations between Brussels and Washington were always going to be troubled. What's more, the creation of a large and powerful fortress Europe offered its politicians something else, the chance to return to the fun and games of great power politics.

They have jumped at the opportunity. Speaking back in 2001, some time before 9/11 and the bitter dispute over Iraq, Swedish Prime Minister Göran Persson (who then also held the EU's rotating presidency) provided a perfect example of the paranoia and ambition that underpins this European dream. The EU was, he claimed "one of the few institutions we can develop as a balance to U.S. world domination."

Brandishing the American bogeyman was always inevitable. Condoleezza Rice may claim to have discovered a European "identity," but outside the palaces, parliaments, and plotting of the continent's politicians such an identity is a frail, feeble, synthetic thing. The preamble to the EU constitution refers to a Europe "reunited after bitter experiences," a phrase so bogus that it would embarrass Dan Brown. Unless I missed something in my history classes "Europe" has never been one whole. There is nothing to reunite. A Swede, even Göran Persson, is a Swede long before he is a "European." Naturally, the framers of the constitution have done their best to furnish a few gimcrack symbols of their new Europe (there's (Article I-8) a flag, a motto ("United in Diversity), an anthem, and, shrewdly in a continent that likes its vacations, a public holiday ("Europe Day") and perhaps in time these will come to mean something, but for now they are poor substitutes for that emotional, almost tribal, idea of belonging that is core to an authentic sense of national identity.

But if the EU has had only limited success in persuading its citizens what they are, it has done considerably better in convincing them as to what they are not: Americans. Writing in 2002 about the "first stirrings" of EU patriotism, EU Commissioner Chris Patten could only come up with two examples: "You can already feel [it], perhaps, in the shared indignation at US steel protection...You can feel it at the Ryder Cup, too." It's significant that when Patten gave examples of this supposed European spirit, he could only define it by what it was against (American tariffs and American golfers) rather than by what it was for. It is even more striking that in both cases the "enemy" comes from one place—the U.S. If Patten had been writing in 2005 he would, doubtless, have added opposition to the war in Iraq to his list—and he would have been right to do so.

This is psychologically astute: The creation of a common foe (imagined or real) is a good way to unify a nation, even, possibly, a bureaucratically constructed "nation" like the EU. Choosing the U.S. as the designated rival comes with two other advantages. It fits in nicely with the existing anti-American bias of much of the EU's ruling class and it will strike a chord with those many ordinary Europeans who are genuinely skeptical about America, its ambitions and, yes, what it stands for.

Insofar, therefore, as it represents another step forward in the deeper integration of the EU, the ratification of the constitution cannot possibly, whatever Secretary Rice might say, be good news for the U.S. How deep this integration will be remains a matter of dispute. In Euro-skeptic Britain, Tony Blair's government has denied that the document has much significance at all, but without much success. At the same time, claims that the ratification of the EU constitution will of itself represent the creation of a European superstate are overblown. It won't, but it will be another step in that direction, and, based on past precedent, we can be sure that the EU's fonctionnaires will use the vacuum created by all those helpful ambiguities in the constitution's text to push forward the federalizing project as fast and as far as possible.

It is, of course, up to Europeans to decide if this is what they want. Any attempt by the Bush White House to derail the ratification process would backfire, but that does not mean that the administration should be actively signaling its support for this dreadful and damaging document. Secretary Rice argues that the integration represented by the passing of the constitution would be a "good development." The opposite is true. If the EU (which has a collective agenda primarily set by France and Germany) does increasingly speak with one voice, Washington is unlikely to enjoy what it hears.

The constitution paves the way for the transfer of increasing amounts of defense and diplomatic activity from Europe's national capitals to Brussels. Article 1-16 commits all member states to a "common foreign and security policy." "Member states" are required to "actively and unreservedly support the Union's common foreign and security policy in a spirit of loyalty and mutual solidarity and shall comply with the Union's actions in this area. They shall refrain from action contrary to the Union's interests or likely to impair its effectiveness." In a recent radio interview, Spanish prime minister Jose Zapatero explained how this might work: "we will undoubtedly see European embassies in the world, not ones from each country, with European diplomats and a European foreign service...we will see Europe with a single voice in security matters. We will have a single European voice within NATO."

And the more that the EU speaks with that one voice, the less will be heard from those of its member states more inclined to be sympathetic to America. And as to what this would mean, well, French Green politician Noel Mamère put it best in the course of an interview last week: "The good thing about the European constitution is that with it the United Kingdom will not be able to support the United States in a future Iraq."

And would that, Secretary Rice, be a "good development"?