On August 3, 1914, twenty-two of England’s best public school cricketers gathered for the annual schools’ representative match. The game ended the following evening. Britain’s ultimatum to Germany expired a few hours later. Seven of those twenty-two would be dead before the war was over. Anthony Seldon and David Walsh’s fine new history of the public schools and the First World War bears the subtitle “The Generation Lost” for good reason.

Britain neither wanted nor was prepared for a continental war. Its armed forces were mainly naval or colonial. The regular army that underwrote that ultimatum was, in the words of Niall Ferguson, “a dwarf force” with “just seven divisions (including one of cavalry), compared with Germany’s ninety-eight and a half.”

Britain’s more liberal political traditions, so distinct then—and now—from those of its European neighbors, had rendered peacetime conscription out of the question, but manpower shortages during the Boer War and growing anxiety over the vulnerability of the mother country itself led to a series of military reforms designed to toughen up domestic defenses. These included the consolidation of ancient yeomanry and militias into a Territorial Force and Special Reserve. The old public-school “rifle corps,” meanwhile, were absorbed into an Officers’ Training Corps and put under direct War Office control.

Most public schools signed up for this, and by 1914 most had made “the corps” compulsory. Some took it seriously. Quite a few did not. Stuart Mais, the author of A Public School in Wartime (1916), wrote that Sherborne’s prewar OTC was seen as “a piffling waste of time . . . playing at soldiers” that got in the way of cricket. Two decades later, Adolf Hitler cited the OTC to a surprised Anthony Eden (then Britain’s foreign secretary) as evidence of the militarization of Britain’s youth. It “hardly deserved such renown,” drily recalled Eden (in his unexpectedly evocative Another World 1897–1917), “even though the light grey uniforms with their pale blue facings did give our school contingent a superficially Germanic look.”

And yet this not-very-military nation saw an astonishing response to the call for volunteers to join the fight. By the end of September 1914 over 750,000 men had enlisted. But where were the officers to come from? A number of retired officers returned to the colors, and the Territorials boasted some men with useful experience, but these were not going to be close to sufficient numbers. The army turned to public-school alumni to fill the gap. In theory, this was because these men had enjoyed the benefit of some degree of military training, however inadequate, with the OTC, but in truth it was based on the belief of those in charge, themselves almost always former public schoolboys, that these chaps would know what to do. Looked at one way, this was nothing more than crude class prejudice; looked at another, it made a great deal of sense. In the later years of the war, many officers (“temporary gentlemen” in the condescending expression of the day) of humbler origins rose through the ranks, but in its earlier stages the conflict was too young to have taught the army how best to judge who would lead well. In the meantime, Old Harrovians, Old Etonians, and all those other Olds would have to do.

To agree that this was not unreasonable implies a level of acceptance of the public school system at its zenith utterly at odds with some of the deepest prejudices festering in Britain today. British politics remain obsessed with class in a manner that owes more to ancient resentments than any contemporary reality. A recent incident, in which a columnist for the far left Socialist Worker made fun of the fatal mauling of an Eton schoolboy by a polar bear (“another reason to save the polar bears”), is an outlier in its cruelty, but it’s a rare week that goes by in which a public school education is not used to whip a Tory cur, as David Cameron (Eton) knows only too well.

Under the circumstances it takes courage to combine, as Seldon and Walsh do, a not-unfriendly portrait of the early twentieth-century public schools (it should be noted that both men are, or have been, public schoolmasters) with a broader analysis that implies little sympathy for the sentimental clichés that dominate current British feeling—and it is felt, deeply so—about the Great War: Wilfred Owen and all that. It is not necessary to be an admirer of the decision to enter the war or indeed of how it was fought (I am neither) to regret how Britain’s understanding of those four terrible years has been so severely distorted over the past decades. Brilliantly deceptive leftist agitprop intended to influence modern political debate has come to be confused with history.

Oh! What a Lovely War smeared the British establishment of the 1960s with the filth of Passchendaele and the Somme. Similarly, the caricature of the war contained in television productions such as Blackadder Goes Forth (1989) and The Monocled Mutineer (1986) can at least partly be read as an angry response to Mrs. Thatcher’s long ascendancy. Coincidentally or not, the late 1980s also saw the appearance of The Old Lie: The Great War and the Public-School Ethos by Peter Parker. For a caustic, literary, and intriguing—if slanted—dissection of these schools’ darker sides, Parker’s book is the place to go.

Seldon and Walsh offer a more detailed and distinctly more nuanced description of how these schools operated, handily knocking down a few clichés on the way: There were flannelled fools aplenty, but there was also the badly wounded Harold Macmillan (Eton), “intermittently” reading Aeschylus (in Greek) as he lay for days awaiting rescue in a shell hole. Aeschylus was not for all, but a glance at the letters officers wrote from the front is usually enough to shatter the myth of the ubiquitous philistine oaf. There was much more to the public schools than, to quote Harrow’s most famous song, “the tramp of the twenty-two men.”

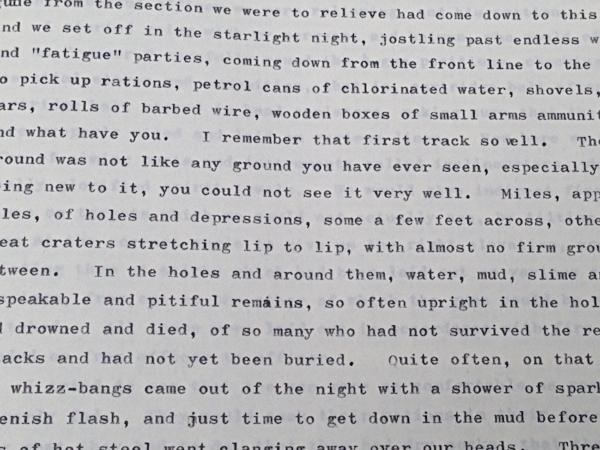

But however harsh a critic he may be (“that men died for an ethos does not mean that the ethos was worth dying for”), Parker is too honest a writer not to acknowledge the good, sometimes heroic, qualities of these hopelessly ill-trained young officers and the bond they regularly forged across an often immense class divide with the troops that they led. “I got to know the men,” wrote my maternal grandfather Richard Ropner (Harrow, Machine Gun Corps) in an unpublished memoir half a century later, “I hope they got to know me.” In many such cases they did. It is tempting to speculate that such bonds (easier to claim, perhaps, de haut than en bas) may have been more real in the eyes of the commanders than of the commanded, but there is strong evidence to suggest that there was nothing imaginary about them. Men died for their officers. Officers died for their men.

My grandfather owned a set of memorial volumes published by Harrow in 1919. Each of the school’s war dead is commemorated with a photograph and an obituary. It is striking to see how frequently the affection with which these officers—and they almost all were officers—were held by their men is cited. Writing about Lieutenant Robert Boyd (killed at the Somme, July 14, 1916, aged twenty-three), his company commander wrote that Boyd’s “men both loved him and knew he was a good officer—two entirely different things.” This subtle point reflects the way that the public school ethos both fitted in with and smoothed the tough paternalism of the regular army into something more suited to a citizen army that now included recruits socially, temperamentally, and intellectually very different from that rough caste apart, Kipling’s “single men in barricks.”

The public schools relied heavily on older boys to maintain a regime that had come a long way from Tom Brown’s bleak start. This taught them both command and, in theory (Flashman had his successors), the obligations that came with it. That officers were expected both to lead and care for their men was a role for which they had thus already been prepared by an education designed, however haphazardly, to mold future generations of the ruling class. Contrary to what Parker might argue, these schools had not set out to groom their pupils for war. But the qualities these institutions taught—pluck, dutifulness, patriotism, athleticism (both as a good in itself and as a shaper of character), conformism, stoicism, group loyalty, and a curious mix of self-assurance and self-effacement—were to prove invaluable in the trenches as was familiarity with a disciplined, austere, all-male lifestyle.

There was something else: The fact that many of these men had boarded away from home, often from the age of eight, and sometimes even earlier, meant that they had learned how to put on a performance for the benefit of those who watched them. A display of weakness risked transforming boarding school life into one’s own version of Lord of the Flies. That particular training stayed with them on the Western Front: “I do not hold life cheap at all,” wrote Edward Brittain (Uppingham), “and it is hard to be sufficiently brave, yet I have hardly ever felt really afraid. One has to keep up appearances at all costs even if one is.” It was all, as Macmillan put it, part of “the show.”

There are countless examples of how stiff that upper lip could be, but when Seldon and Walsh cite the example of Captain Francis Townend (Dulwich), even those accustomed to such stories have to pause to ask, who were these men?: “Both legs blown off by a shell and balancing himself on his stumps, [Townend] told his rescuer to tend to the men first and said that he would be all right, though he might have to give up rugby next year. He then died.”

Pastoral care was all very well, but the soldiers also knew that, unlike the much-resented staff officers, their officers took the same, or greater, risks that they did. This was primarily due to the army’s traditional suspicion that the lower orders—not to speak of the raw, half-trained recruits who appeared in the trenches after 1914—could not be trusted with anything resembling responsibility, but it also reflected the officers’ own view of what their job should be. And so, subalterns (a British army term for officers below the rank of captain), captains, majors, and even colonels led from the front, often fulfilling, particularly in the case of subalterns, a role that in other armies would be delegated to NCOs. The consequences were lethal. Making matters worse, the inequality between the classes was such that officers were on average five inches taller than their men, and, until the rules were changed in 1916, they always wore different uniforms too. The Germans knew who to shoot. The longer-term implications of this cull of the nation’s elite may have been exaggerated by Britons anxious to explain away their country’s subsequent decline, but the numbers have not: some 35,000 former public schoolboys died in the war, a large slice of a small stratum of society.

Roughly eleven percent of those who fought in the British army were killed, but, as Seldon and Walsh show, the death rate among former public schoolboys (most of whom were officers) ran at some eighteen percent. For those who left school in the years leading up to 1914 (and were thus the most likely to have served as junior officers) the toll was higher still. Nearly forty percent of the Harrow intake of the summer of 1910 (my grandfather arrived at the school the following year) were not to survive the war. Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War (2010) by John Lewis-Stempel is an elegiac, moving, and vivid account of what awaited them. Lewis-Stempel explains his title thus: “The average time a British Army junior officer survived during the Western Front’s bloodiest phases was six weeks.”

To Lewis-Stempel, a fierce critic of those who see the war as a pointless tragedy, the bravery and determination of these young officers made them “the single most important factor in Britain’s victory on the Western Front,” a stretch, but not an altogether unreasonable one, and he is not alone in thinking this way. The British army weathered the conflict far better—and far more cohesively—than did those of the other original combatants, and effective officering played no small part in that.

Lewis-Stempel attributes much of that achievement to the “martial and patriotic spirit” of the public schools, a view of those establishments with which Parker would, ironically, agree, but that is to muddle consequence with cause. Patriotic, yes, the schools were that, as was the nation—being top dog will have that effect. But, like the rest of the country, they were considerably less “martial” than Britain’s mastery of so much of the globe would suggest. A public school education may have provided a good preparation for the trenches, but it did not pave the way to them. That so many alumni came to the defense of their country in what was seen as its hour of need ought not to form any part of any serious indictment against the schools from which they came. That they sometimes did so with insouciance and enthusiasm that seems remarkable today was a sign not of misplaced jingoism, but of a lack of awareness that, a savage century later, it’s difficult not to envy.

And when that awareness came, they still stuck it out, determined to see the job done. Seldon and Walsh write that “It was the ability . . . to endure which underpinned the former public schoolboys’ leadership of the army and the nation.” Perhaps it would have been better if they had had been less willing to endure and more willing to question, but that’s a different debate. To be sure, there was plenty of talk of the nobility of sacrifice—and of combat—but, for the most part, that was evidence not of a death wish or any sort of bloodlust, but of the all too human need to put what they were doing, and what they had lost, into finer words and grander context.

And that they clung so closely to memories of the old school—to an extent that seems extraordinary today—should come as no surprise. These were often very young men, often barely out of their teens. School, especially for those who had boarded, had been a major part of their lives, psychologically as well as chronologically. “School,” wrote Robert Graves (Charterhouse), “became the reality, and home life the illusion.” And now its memory became something to cherish amid the mad landscape of war.

They wrote to their schoolmasters and their schoolmasters wrote to them. They returned to school on leave and they devoured their school magazines. They fought alongside those who had been to the same schools and they gave their billets familiar school names. They met up for sometimes astoundingly lavish old boys’ dinners behind the lines, including one attended by seventy Wykehamists to discuss the proposed Winchester war memorial. The names of three of the subalterns present would, Seldon and Walsh note, eventually be recorded on it.

So far as is possible given what they are describing, these two authors tell this story dispassionately. Theirs is a calm, thoroughly researched work, lacking the emotional excesses that are such a recurring feature of the continuing British argument over the Great War. That said, this book’s largely uninterrupted sequence of understandably admiring tales could have done with just a bit more counterbalance. For that try reading the recently published diaries written in a Casualty Clearing Station by the Earl of Crawford (Private Lord Crawford’s Great War Diaries: From Medical Orderly to Cabinet Minister) with its grumbling about “ignorant and childish” young officers arousing “panic among the men [with] their wild and dangerous notions.”

Doubtless the decision by Captain Billy Neville (Dover College) to arrange for his platoons to go over the top on the first day of the Somme kicking soccer balls is something that Crawford would have included amongst the “puerile and fantastic nonsense” he associated with such officers. Seldon and Walsh, by contrast, see this—and plausibly so—not as an example of Henry Newbolt’s instruction to “Play up! play up! and play the game!” being followed to a lunatic degree, but rather as an astute attempt by Neville to give his soldiers some psychological support. “His aim was to make his men, who he knew would be afraid, more comfortable.” Better to think of those soccer balls than the enemy machine guns waiting just ahead. Nineteen thousand British troops were killed that day, including Neville. He was twenty-one.

Crawford was a hard-headed, acerbic, and clever Conservative, but occasionally his inner curmudgeon overwhelmed subtler understanding, as, maybe, did his location behind the lines, fifteen miles from where these officers shone. Nevertheless, one running theme of his diaries, the luxuries that some of them allowed themselves (“yesterday a smart young officer in a lofty dogcart drove a spanking pair of polo ponies tandem past our gate”) touches on a broader topic—the stark difference in the ways that officers and men were treated—that deserves more attention than it gets in Public Schools and the Great War. Even the most junior officers were allocated a “batman” (a servant). They were given more leave, were paid a great deal more generously, and, when possible, were fed far better and housed much more comfortably than their men. Even in a more deferential age, this must have rankled. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Parker dwells on this issue in more detail than Seldon and Walsh, but, fair-minded again, agrees that what truly counted with the troops was the fact that “when it came to battle [the young officers’] circumstances were very much the same as their own.”

They died together. And they are buried together, too, not far from where they fell. As the founder of the Imperial War Graves Commission explained, “in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, the officers will tell you that, if they are killed, they would wish to be among their men.”

A century later, that’s where they still are.